Picketers stood between me and the clinic doors. They held signs and although I couldn’t make them out, I knew the messages were anti-abortion. Luckily, I was able to slip in a back entrance. I went there to terminate a pregnancy for $450.

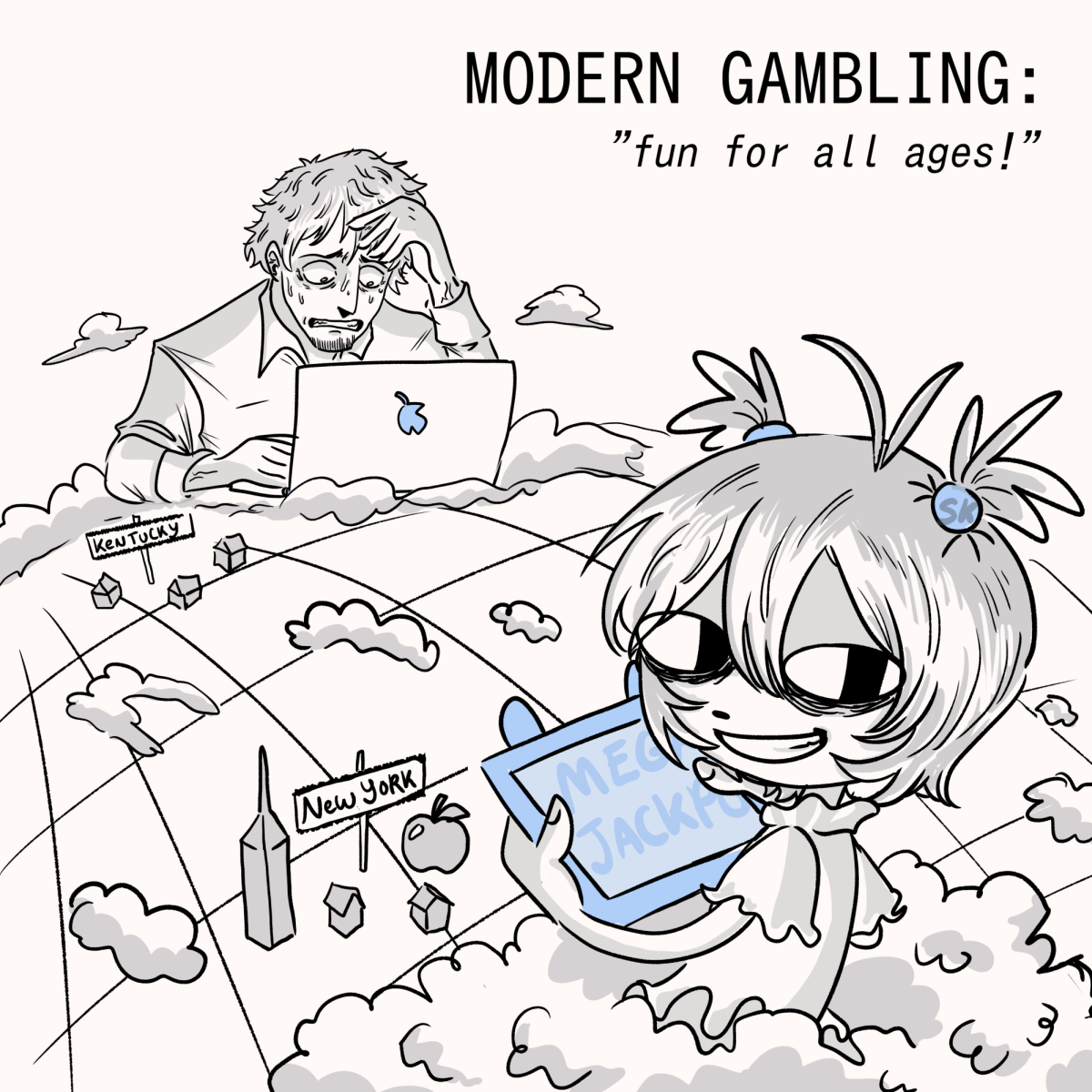

Had I shelled out for birth control, this probably wouldn’t have happened. But I didn’t want to spend the $15 per month it would have cost me then. Now, thanks to recent federal legislation, birth control costs up to four times as much to buy through college health centers.

Through a quirk in the 2005 Deficit Reduction Act, drug companies no longer have incentive to sell discounted birth control to university clinics.

Even though President Bush signed the act last February, the Ada B. Vielmetti Health Center wasn’t affected until recently.

That’s because the health center, like so many across the country, had stockpiled birth control. But now Vielmetti’s discounted stockpile is gone, said Jan Nolan, the health center’s pharmacist.

Before the Deficit Reduction Act went in effect, birth control pills at the health center ranged from $7 to $15. Now a month’s supply costs between $20 and $50. The contraceptive ring that used to cost about $15 now costs about $50. Even the Plan B, or morning after pill, doubled in price.

The majority of students getting birth control from the health center pay full price, Nolan estimated. Students pay similar amounts off campus, so the Deficit Reduction Act has made local pharmacies more competitive with university health clinics.

As a student relegated to part-time minimum wage work, I am still incensed at how expensive birth control is. Wal-Mart’s price range is nearly identical to the health center’s. ShopKo is a little pricier, with their lowest price starting around $30.

Many students are willing to pay full price for birth control, rather than allowing health insurance to cover it, to prevent their parents from finding out that they’re taking contraceptives.

It is not typical for college-age women to have insurance independent of their parents. Even if they do, birth control may not be covered. I have to pay full price because my Chicago-based health insurance won’t fill my prescription here at NMU. Due to this poorly thought-out piece of legislation, my choices are to pay more money than I can afford, be abstinent or take foolish risks.

The Deficit Reduction Act was designed to slow spending growth in government programs. Clearly, college women’s pockets were not taken into account.

Rather than remaining disenchanted by the aftermath of this legislation, the American College Health Association (ACHA) is being proactive. The ACHA National College Health Assessment director, Mary Hoban, said the way to fix this is to get Congress to pass legislation that corrects the quirk in the Deficit Reduction Act.

Congress needs to make a correction that includes college health clinics as a charitable entity again.

Nolan said she foresees the price increase prohibiting people from getting prescriptions. And that means more women can look forward to being where I was two years ago- running a gauntlet of protestors to terminate an unwanted pregnancy.

I’m living proof of how boycotting birth control will backfire. Let our state representatives know how the Deficit Reduction Act is forcing you to spend four times more on birth control.

You can e-mail Michigan State Representative Steven Lindberg at [email protected]