How America’s favorite caffeinated beverage makes it to your local Starbucks

Most mornings, afternoons and evenings I stop by the convenient Starbucks on campus to order a tall coffee, black. On a good day it consists of 12 ounces of fresh-ish, unburned coffee and costs $1.45. According to the National Coffee Association USA’s 2010 national coffee drinking trends study, 56 percent of U.S. adults consume coffee daily. In total, the U.S. spends about $40 billion on coffee per year. I tend to think I drink a little more than average, judging by my heart rate and bank statements, but this story isn’t about my caffeine habit. This is the story of the steaming black mud in  my cup: where it came from and how it got here. This is the story of my $1.45: where it passes and eventually rests, long after my cup is emptied.

my cup: where it came from and how it got here. This is the story of my $1.45: where it passes and eventually rests, long after my cup is emptied.

In 2013, Starbucks imported 396 million pounds of green, or unroasted, coffee beans from 27 countries. Starbucks boasts 95 percent of this was ethically sourced in coordination with its Coffee and Farmer Equity Practices, through Fairtrade or other third-party verified systems.

While coffee is an important export for many developing equatorial countries, its leading producer is Brazil, which produced 2.7 million tons of green coffee in 2011, nearly a third of the global market according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. In 2011, Brazil’s coffee exports totaled 1.8 million tons, one and a half times as much coffee as the U.S. imported on average between 2006-10, according to the Fairtrade Foundation. These 1.8 million tons comprise 3.4 percent of Brazil’s total exports and are valued at 8.7 million USD. While not the bulk of the Brazilian economy, which is among the largest in the world, these exports are an essential source of beans for thirsty consumers around the world and an important means of livelihood for many Brazilians; unfortunately, where the profits from these exports go is less uplifting.

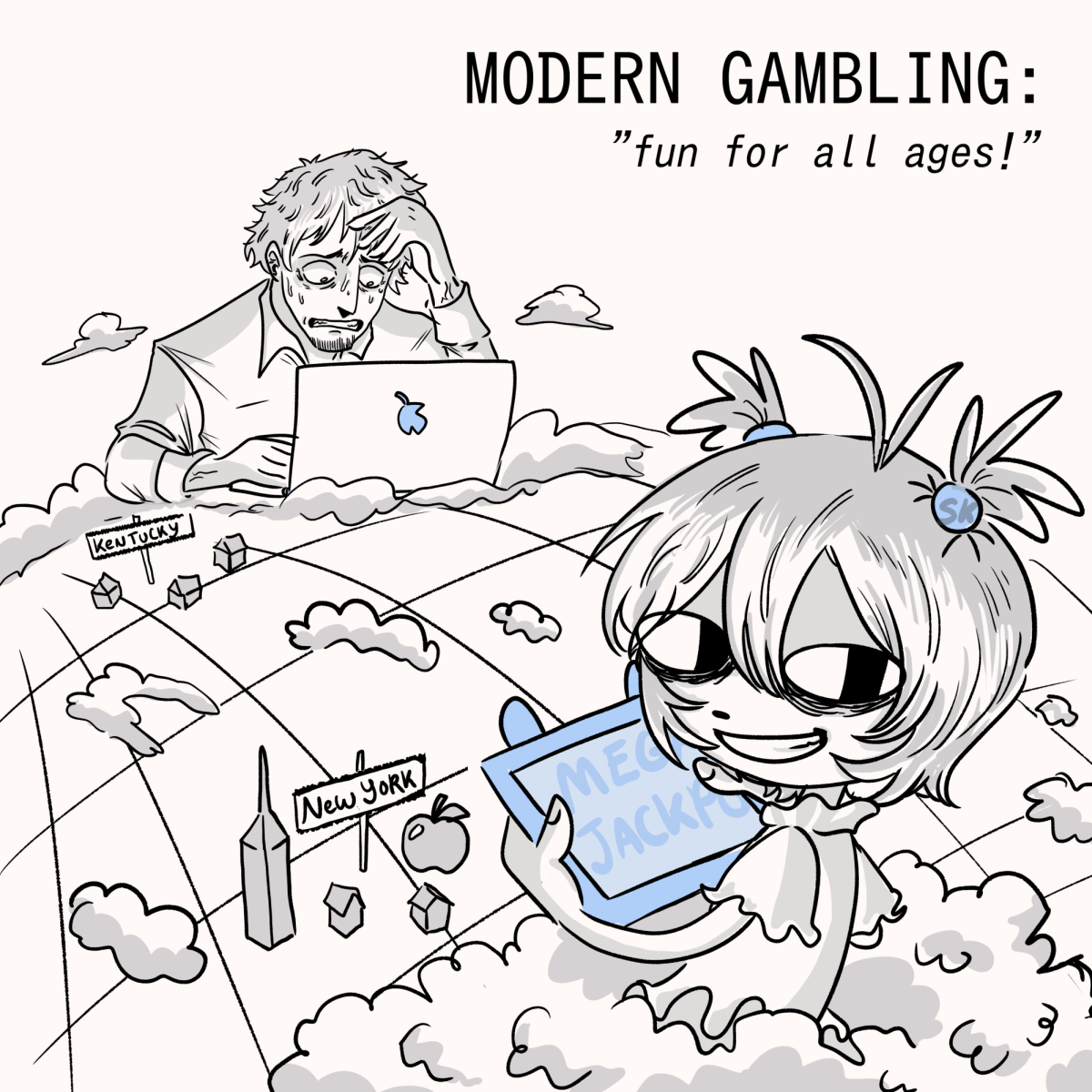

How to ethically source and provide coffee to consumers is a complicated issue. The Fairtrade Foundation, an organization seeking to ensure coffee producers earn a fair wage under humane conditions, has addressed these issues. And while Fairtrade is often lauded for its efforts to provide ethically sourced goods to consumers, it’s a controversial issue with no clear consensus as to its efficacy. Coffee production is an appealing and accessible avenue for some nations; however, it has maintained a problematic reputation ethically. Many of the damaging aspects of cultivation associated with historical colonialism have persisted due to the necessity for these countries to remain competitive in a world market which has few economic opportunities for developing nations besides the exploitation of natural resources and inexpensive labor.

Returning Brazil, according to the Fairtrade Foundation, only six percent of Fairtrade coffee producer organizations were in Brazil in 2011, just five percent of Fairtrade coffee exports worldwide. Even more troubling, the entirety of Fairtrade coffee exports totaled only 103,000 tons – hardly a single drip into the cup.

It seems intuitive that using a premium on coffee sales to pay cultivators and workers better wages and to develop infrastructure and services is a good thing; however, it is hard to quantify these benefits since they include quality of life aspects in addition to monetary concerns and because Fairtrade producer organizations are formed from already successful producers.

At the bitter end, I know what sort of place my coffee has come from and a little about its broad economics, but very little about where my $1.45 went. Comparing the $40 billion the U.S. spends annually on coffee to my roughly calculated $6 million worth of coffee imports to the country, it might be a little painful to swallow this as a great economic opportunity for farmers in Brazil, Vietnam or Ethiopia; most of the money circulates through the hands of service employees, corporate coffee magnates and commodities traders. But as long as there is demand for hot, liquid stimulant and entrepreneurs thirsty for profit, there will be farmers willing to dedicate their backs to our coffee in hopes of making enough money to get ahead, have security, or just survive.