“The Social Network,” a movie about the creators of Facebook, is coming out on Oct. 1. The movie is about how Mark Zuckerberg created the social networking site Facebook in his dorm room at Harvard in 2005. According to Rolling Stone, the movie “defines the decade.” I find it unfortunate that such statements can be made, even argued for.

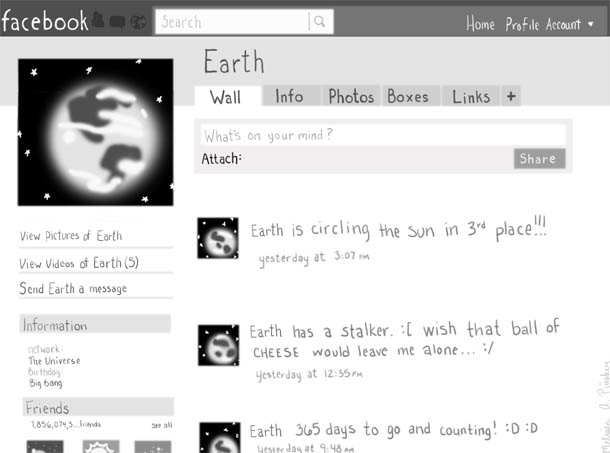

Social media outlets were conceived as extensions for interpersonal communication. They were designed, as their very name implies, as a social tool. Now, it seems, we have let social media define us, instead of the other way around.

A recent study referenced in a dailymail.co.uk article found that excessive Facebook use is correlated to narcissism. Another study, referenced in the same article, showed that students who use Facebook while they study, even just having it in the background, have grades 20 percent lower on average than non-users. With over 500 million people on Facebook, that’s a lot of slipping grades.

Our use of Facebook, it seems, has allowed us to be consumed by constant updates of people on our friends list. We have begun looking at life as entertainment.

Social media websites like Facebook have given us the chance to communicate ideas, facts and details of our lives instantaneously across the world. If used properly and responsibly, there is nothing wrong with social media sites. They allow us to communicate with friends and relatives we might otherwise be out of contact with.

The biggest problem, I think, in using social media websites is that no one seems to know how we should use it. People use them as a blog, a personal diary, a true internet record of their lives or to network with fellow students or future employers, while still others use it to inform friends of their weekend night plans.

Unfortunately, I think, too many people use Facebook for every reason in the previous paragraph. The result is anarchy.

When the automobile was invented, its creators had no way of predicting the outcomes of that invention. They could not have perceived paved roads, air pollution, traffic lights, car pools, bus routes, cab drivers and everything else that developed as a result of the invention of the automobile.

Similarly, the creators of social media sites –– like Mark Zuckerberg in Facebook’s case or Tom Anderson, co-founder of MySpace –– had no way of predicting how their creations would affect modern communication. The idea was positive. Wouldn’t it be great if we could communicate with the people in our lives on one site, with photos, status updates and a blog feature?

But once they were created, the drama of human communication started. You don’t tell your priest you’ve been sinning all weekend, just like you don’t let your boss know you went to that Packers game when you said you were sick. But there it is: the photo proof, someone’s tagged you in a photo and there isn’t much you can do but untag it, then watch helplessly as someone else tags you again.

Another problem comes in what we choose to communicate rather than how we communicate it. Do we really want our ex-girlfriends from high school or that kid who sat next to us in sixth grade to know that we drank the equivalent of Lake Superior in whiskey last night?

These questions, while seemingly obvious, seem to be rarely asked. People update their status without thinking about who can see them, or upload photos without contemplating consequences.

We, as consumers and users of the internet, have allowed Facebook and other sites like it (Twitter, MySpace) to permeate our lives. Yet very few people seem to be asking why.

In 1985, a book called Amusing Ourselves to Death was written by Neil Postman. The book depicts the author’s fears that television will change society to the point where every aspect of our lives –– whether politics, religion, personal relationships or education –– will be dumbed down into sound bites. Twenty five years later, we have the result of those fears, and it is called social media. We need to return to the days when social media was a tool, not something which defined us.

So yes, maybe “The Social Network” does define our decade. But the question few seem to be asking is: should we allow social media to define the next decade? Are we doomed to throw every aspect of our lives into an internet soup of information, awkward acquaintances and people we used to know? I, for one, hope the answer to these questions is a resounding no.

James • Oct 4, 2010 at 12:44 pm

In the Facebook equation, the users are the product and not the consumer. Facebook was invested in heavily for a reason. Do not believe for a second that these investors are not out to make money.

If you like Coca Cola, Wal-Mart, and out sourced jobs, keep your Facebook account. That comparison is ridiculous, but those examples along with Facebook are making someone loads of money at humanities expense. High fructose corn syrup, perceived obsolescence, poor quality of life, and a perfect marketing tool that invades privacy are examples that are almost no different from one another.

here is a helpful link:

http://www.facebook.com/help/?search=i%20want%20to%20permanently%20delete%20my%20account

Traci Toguchi • Oct 3, 2010 at 2:41 am

Josh: Why not? Why shouldn’t it permeate lives? Perhaps because it is filling voids which should be addressed, rather than blindly carrying on from one obsession (“fad”) to another.

Instead of merely allowing this to take over for the reason of “why not”, perhaps looking at “why” would allow people to look at what is being avoided, and take time to deal with that. Yes, it’s tough and most people would rather not deal with reality, acceptance, and work toward truly developing their inner strength, however, if they do, their self-esteem will thrive, and true, innate happiness will be the ultimate result.

When moving forward, it is important to look back, reflect and learn (why history is studied).

Steve • Oct 2, 2010 at 2:50 pm

Only if we succumb to the false promises (self-actualization, self-esteem, etc.); that is, if we allow it to define us and our place in society.

Didaskalos • Oct 1, 2010 at 4:58 pm

Dan Yoder’s “10 Reasons To Delete Your Facebook Account” in Business Insider [ http://www.businessinsider.com/10-reasons-to-delete-your-facebook-account-2010-5 ] is an article worth reading.

An intriguing alternative: “Diaspora: It’s no Facebook . . . Yet” [ http://blogs.computerworld.com/16974/diaspora_its_no_facebook_yet ]

Josh • Oct 1, 2010 at 3:12 pm

“We, as consumers and users of the internet, have allowed Facebook and other sites like it (Twitter, MySpace) to permeate our lives. Yet very few people seem to be asking why.”

Why not?

There are always people predicting the downfall of humanity due to the latest fad/invention. We will adjust and move on, just as we have done countless times before. You can’t go back, only forward.