Thursday, March 20, 2014 – Marquette, MI – To address outcry by individuals and conservation groups over recent proposed changes to the Eagle Mine’s Groundwater Discharge Permit (GWDP), a public hearing will be held at 6 p.m. Tuesday, March 25 at Westwood High School in Ishpeming, Mich.

At the hearing, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) will present information in response to claims the new permit will not adequately protect groundwater, followed by a question-and-answer session and a formal public hearing.

The MDEQ, as well as Save the Wild U.P. (SWUP), the Yellow Dog Watershed (YDWP) and other organizations, strongly encourage the public to participate in this forum in order to educate themselves and contribute to the dialogue.

“We’re not ashamed of what we do. We think we’ve done good work in following the law,” MDEQ District Supervisor Steve Casey said. “We want a chance to explain that to people, [and] people who want to hear and listen will actually appreciate that.”

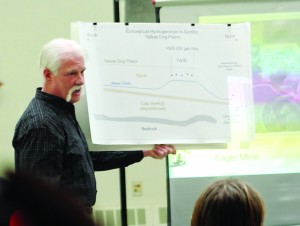

Critics of the new permit, which include SWUP, the YDWP, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC), Huron Mountain Club and the National Wildlife Federation, among others, voiced vehement opposition to the new permit at an educational panel presented by SWUP on Tuesday, March 18 at Peter White Public Library.

Chuck Brumleve, environmental mining specialist for KBIC, said the mining operation, if not regulated properly, will pump metals and contaminants into Lake Superior and the Salmon Trout River. He also warned about the environmental dangers posed by sulfide mining and acid mine drainage.

“We feel that the state should be very conservative in following its statutes and rules,” he said, “because there is such a potential for harm and damage to the area.”

Eagle Mine Media Relations Director Dan Blondeau said the permit must be renewed every five years, and this is just part of that process.

“The application includes information that reflects the pre-mining water conditions recorded over the last decade,” he said. “Most importantly, the new permit will maintain the high standards set in the original permit, and water quality will not be lowered.”

But YDWP Executive Director Mindy Otto said the MDEQ is setting maximum daily limits on only five constituents, while the rest will be self-reported by the mine.

“[This] essentially sets no legal limit on over 30 other potential sources of pollution, including nickel, sulfate and uranium,” Otto said. “It could take a few years for groundwater pollution to reach surface waters, but I am definitely concerned with the output of heavy metals as they will have a more immediate toxic impact on the surrounding indigenous aquatic life and everything that feeds on that.”

Jessica Koski, mining technical assistant for the natural resources department of the KBIC, said this permit is less protective of underground water sources than the initial permit challenged by KBIC and coalition partners in 2007.

“Such lax reporting requirements are unacceptable when discharges will enter the aquifer at a rate of 504,000 gallons per day,” Koski said “How [will] the company ever be found in violation of discharge limits if there are no numeric permit limits for many constituents? Sounds pretty convenient for the permit holder, in this case, a Canadian mining company with no previous mining experience in the United States.”

In fact, the Superior Watershed Partnership (SWP), the conservation group in charge of independent monitoring through the Community Environmental Monitoring Project (CEMP), has recorded at least 47 violations of the initial permit since monitoring began in 2008. The violations occurred in such constituents and characteristics as pH, arsenic, copper, lead, molybdenum, silver and vanadium.

No citations or fees have been levied by the MDEQ at Rio Tinto nor Lundin Mining Company, who bought the mine from Rio Tinto in June 2013. Critics of the proposed draft said the changes to the permit adjust what is considered acceptable levels of contaminants to match early violations as an alternative to enforcement.

But Casey said pre-existing natural conditions at the mine already exceeded the limits set by the first permit.

“Most of the violations occurred before the Eagle Mine even started discharging, so they were obviously caused by natural conditions,” he said. “The permit limits for the groundwater were set so tight that even the natural conditions didn’t meet them.”

Lundin, in a “Frequently Asked Questions” section posted online this month responded to the presence of uranium in groundwater, saying, “Uranium is a naturally occurring element found in all rock, soil and water. While the permit does not include a limit for uranium, it does require Eagle to monitor and report uranium to state regulators monthly.”

It also asked the question, “Is it true that Eagle has violated its current permit?”

The answer was, “Eagle has never received a Notice of Violation (NOV) from state regulators.”

“That’s like saying you’ve never sped in your car because you’ve never been caught,” said SWUP President Kathleen Heideman in response. “That doesn’t mean you didn’t speed, it just means that you haven’t been pulled over.”

Brumleve said for the tribe, it’s all about water.

“It is the lifeblood of mother earth and it’s essential to every life form on the earth,” he said. “We should all be ashamed that this state has fish advisories on every body of water in the state. Every stream, every river.”

Lois Gibbs, founder of the Center for Health, Environment and Justice, said she has seen hundreds of communities succeed in cases of poor environmental regulation and negative public health impacts when people put pressure on decision-makers.

“That the Michigan DEQ twice extended the comment period on the renewal of the Eagle project’s Groundwater Discharge Permit shows that people power around this issue is working,” she said. “Polluters fear people who use their collective voice to tell the truth and ask for local control. Remember, it is polite people, who play by the rules and don’t work together for justice, who end up poisoned.”

Once in operations, Eagle Mine will be the only primary nickel mine in the U.S., and is expected to produce 300 million pounds of nickel, 250 million pounds of copper and small amounts of other metals.

Jack Parker (Baltic MI 49963) • Mar 24, 2014 at 5:52 pm

Some say that mercury is everywhere in Michigan, largely because it may be airborne.

Are there any significant bodies of water, excluding springs, where mercury is absent?