Jon Ronson began with himself. In early 2012, Ronson noticed a fake Twitter account under his name was created by three academics who called the feed an “infomorph.” His infomorph was, apparently, a bi-curious gourmand with an appetite for ’90s sitcoms.

He’d see tweets like:

“Going home. Gotta get the recipe for a huge plate of guarana and mussel in a bap with mayonnaise

When Ronson asked for the account to be deleted, the infomorph’s overlords upped the ante.

“#woohoo damn, I’m in the mood for a tidy plate of onion grill with crusty bread. #foodie.”

The feud between Jon Ronson and @Jon_Ronson culminated in the journalist’s fans tweeting hateful, occasionally violent diatribes directed at the infomorph’s creators.

@Jon_Ronson was eventually removed and Ronson himself began regretting the reaction from his fans. They didn’t deserve the response and the infomorph didn’t exactly slander the journalist.

So, he embarked on a mission to understand what public shaming means in the age of social media and how it impacts its victims.

He examines Jonah Lehrer, a science writer who plagiarized one word of a Bob Dylan quote (he changed “I’m glad I’m not me” to “I’m glad I’m not that…”), nose dive into a career slaughter when he deliberately avoided claims of his misquoting. He made his downfall far worse than it could have been when he actively avoided its consequences. (He does have a book forthcoming, “The Book of Love,” which has already been targeted as plagiaristic.)

Lehrer becomes a motif throughout the book. He sets the bar for total shaming. But only for his fame.

We meet Anonymous hackers, tech geeks and the son of a Hitler confidante caught in an SS-style sadomasochistic sex ritual. The guy is almost immune to shaming, maybe because he’s lived his life as the son of a Nazi.

We also meet people training (for the hell of it) to be defendants in a courtroom. And a self-help guru who promises that the only way to genuine relationships is through direct, unflinching honesty. (He was featured in Esquire’s 2007 article “I Think You’re Fat.”)

I think this book can cross generations easily. Despite its social media themes throughout, everyone can relate to the emotional reactions to public shaming.

And he laces the history of shaming throughout. (Delaware, apparently, didn’t ban public shaming until 1952.)

There’s nothing too pretentious about Ronson’s writing—he won’t send you to a dictionary, but he won’t leave you hanging on verbosity either. He’s clear, concise and critical.

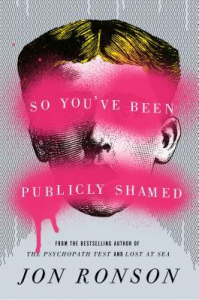

“So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed” left me wondering “where to next?” Are we better for having the power to destroy each others’ self-esteems on such a mass, nearly permanent level? Can we turn around? Or is this justice?