Tuesday was Equal Pay Day, the day women’s earnings finally catch up to men’s from the previous year. Due to wage inequity, for a woman to make the same amount of money as a man does from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, she must work from Jan. 1 to April 12 of the following year.

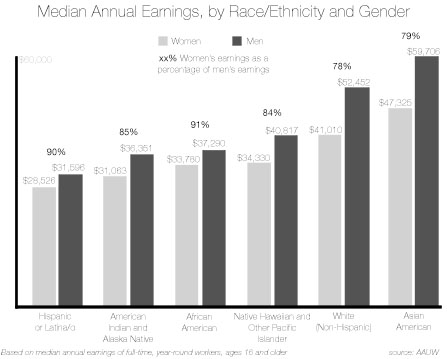

In 2013, women working full time made just 78 percent of what their male counterparts made, according to information collected by the U.S. Census Bureau.

In Michigan, this number drops to 75 percent. When looking at median salaries for men and women in Michigan, the gap is $12,738 annually.

In a 2007 study done by the American Association of University Women (AAUW), one year after university, women were making 82 percent of what their male colleagues with equal education made. Ten years after graduation, it drops to 69 percent.

A portion of this gap can be accounted for because women are more likely than men to go into careers that pay less, such as teaching. Higher paying jobs, like those in the STEM field, are typically male-dominated. This does not account for the entire wage gap, though.

In a study by the AAUW, college major, occupation, economic sector, hours worked, months unemployed since graduation, GPA, type of undergraduate institution, institution selectivity, age, geographical region and marital status were all accounted for, and yet there was still a 7 percent gap between male and female earnings one year after graduation. This grows even higher to a 12 percent unexplained difference 10 years after graduation.

Last semester the AAUW hosted “Start Smart,” a wage negotiation workshop that helps college women gain the skills to negotiate their salary after university.

Mary Snitgen, membership co-chair of the AAUW, said the workshop teaches students how to research the salaries of their desired career in different locations before job interviews, so they are prepared to negotiate. The organization is hoping to host the workshop at NMU again in the fall.

Melissa Sprouse, assistant director of NMU career services, agreed the best way for women to combat pay inequity is to be knowledgeable about the salary range for their career path.

“You want to make sure you’re getting paid what you’re worth, so doing that research on what your wage range should be in is really important,” Sprouse said.

Sprouse recommended websites like CareerOneStop.org, glassdoor.com and the occupational outlook handbook from the U.S. Department of Labor to research wage ranges for occupations in different locations.

The Social Justice Committee at NMU hosted a panel Tuesday called “What’s She Worth” which addressed the concerns surrounding equal pay and how women can proactively seek to fix the gap. The discussion focused on factors leading to gender inequality and outreach that can be done to improve equality. The film “He Named Me Malala” followed the discussion to emphasize the importance of education for women.

Tools like these have helped close the gap in recent years, but there is still a wide disparity between the earnings of men and women. A woman’s race can also greatly affect her salary. A Latina woman can expect to make only 54 percent of what a white male makes, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. An African American woman’s salary is not much higher at 64 percent of a white man’s.

These gaps persist despite the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which meant to abolish discriminate pay based on gender and create equal pay for equal work. The Paycheck Fairness Act, a bill introduced multiple times since 1997, moved to strengthen the Equal Pay Act by punishing employers that unequally paid their employees based on gender. In 2014 the act failed to gain enough votes in the Senate to become law.

“I don’t think that the people in Washington really believe that there is a pay gap because [the women] in Washington, D.C. make 91 percent of what men do,” Snitgen said, referencing the study by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Snitgen said she does believe there’s a positive trend in equal pay, but there is still work to be done.

“It’s going to take more time, it’s going to take more awareness, it’s going to take more courage on the part of women going into the job market,” Snitgen said. “But it’s not easy.”