Young person worry: What if nothing I do matters?

Old person worry: What if everything I do does?

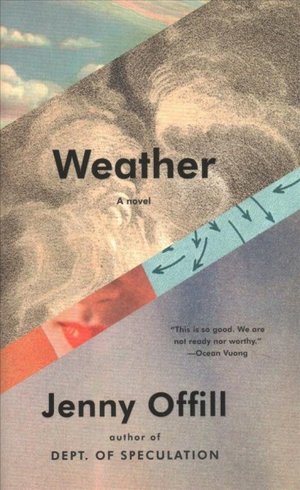

This is just one of the many profundities placed throughout Jenny Offill’s new novel “Weather.” Offill’s most recent novel “Dept. of Speculation” (2014) was a critical homerun. It was a very aptly named novel. “Jenny Offill,” the name, became shorthand for writing that has a masterly, sharp and witty eye, for its ability to spectate. It contains a way of seeing that made you, the reader, more aware of how you saw. It is a writing that sees.

In “Weather,” Offill applies her celebrated eye to the age of information. The novel could be understood as stream-of-consciousness, although it doesn’t run continuously, ethereal, in the traditional way we understand the term. That is: it’s not the endless road of a sentence that is Kerouac, it’s not the wavy vagueness that can be Woolf, and it’s not the scattered hearsay that is Joyce.

What Offill offers in her novel is more akin to a series of individual tweets, although obviously more complex than the average, they are compact and crafted paragraphs, each a main idea. It makes the reading swift and brisk, but also brutal and punctuated. Several paragraphs in a row will contain a section. And these sections themselves represent a contained dilemma or dialogue on a larger idea. There are 200 pages of these sections, and we have a novel.

The paragraphs are comprised of anecdotes. There are many callbacks and threads. But there is also a sort of transcendental association. The famed drummer and writer Questlove, in his book “The Creative Quest,” notes that the internet works by “odd association.” (And all it takes is the Googling of virtually any word, and a brief meditation on the bizarre diversity of results that come up, to prove him right).

The effect it makes one feel is like the humanist or writer was set-up to get absolutely demolished in the age of information. Offill’s narrator can’t aloofly glance over or coldly analyze the data of the world. The heart is too involved, and it’s like watching the heart transform into a pinball, or a puck, being ponged back and forth by anecdote after anecdote, story after story after story. (Go ahead: put this article down and scroll through your Facebook newsfeed. Attempt to deeply care about every article that your thumb touches down on. This is a book like that, and it’s almost too much, but for the buffer that is the timeliness and wittiness and seriousness of Offill’s remarks.)

So, what follows in the novel is a middle-aged woman, Lizzie, raising her very young son with her partner in New York City through the 2016 election. The first part of the novel deals with the classic Offill eye mostly engaging with the nuances of being a parent, wife, and a sister in the 21st century. The novel’s tone becomes more dire when an old friend, Sylvia—the host of the burgeoning climate apocalypse podcast, “Hell and Highwater”—asks Lizzie to become her assistant and primary email replier. Lizzie’s life is then consumed by the realities of the climate crisis and the people who worry about it. In the beginning stages of this, Lizzie jokes with Silvia, “Environmentalists are so dreary.” “I know, I know,” [Silvia] says back.

But it isn’t long until Lizzie’s consciousness, which, set up so brilliantly by Offill, is the very format of the novel, takes on this same dreariness. It reflects, therefore, how content and ideas can permeate any and every thought throughout a day, especially in the social media saturated 2020.

If you’re just walking in on the climate crisis party—and this is me talking to you, dear reader—it is that bad.

Most people walk in the front door of this party. Take a shot. Fill up a beer. Smoke a cigarette on the front porch. They hang out until they forget where they are, and then kind of stumble on home to fend off a hangover in the morning. But this book is different.

This book asks you to explore that house. This book asks you to get lost in that house. This book tells you to find an escape out of the house, because, anyone who’s ended up this deep, can’t really see it, knows it doesn’t exist.

Finally, this book asks you to come down to the basement where the realists are trying to find a way to cope. This book asks you to be real about what’s happening, because a great deal of what’s gotten us into this mess is the pretending that it doesn’t exist. All those party goers who go right back home.

This book can be a lot. And it is a lot. But a lot is happening in the world, and here in Marquette, too. The Marquette County Board of Commissioners has requested that the Lakeshore Drive shoreline be declared a disaster area on the state level due to erosion. Four out of five Great Lakes just recorded the highest water levels ever for the month of February. The heat is coming. The heat is here.