Josh Sharp, an Associate Professor of Biology, first started testing shore waters for E. coli about a year ago but within the past few weeks, he joined a network of labs across the state utilizing their equipment to monitor for COVID-19. Instead of beach water for safe swimming conditions, they are now testing wastewater for a spreading virus.

Various labs throughout the state of Michigan were funded by a $10 million grant through the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy. The grant is aimed to fund “COVID-19 wastewater testing programs. These local efforts have the potential to be an early warning system for the spread of COVID-19 within a specific community or for coronavirus outbreaks on college campuses and at other densely populated facilities,” according to EGLE’s Sept. 16 press release.

“A few of the labs had already started monitoring for COVID-19, especially the labs at Michigan State University. They started adapting some of the technology they were using for water monitoring to look for COVID-19,” Sharp said.

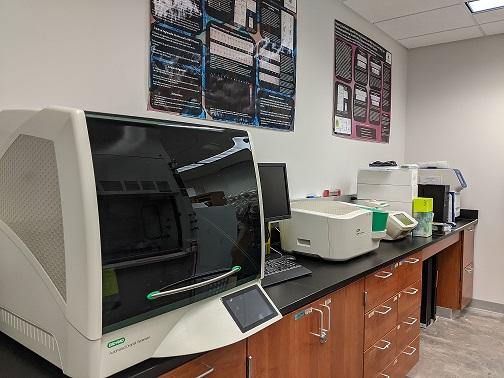

For Sharp and his lab, this necessary switch from E. coli testing to COVID-19 virus testing required new lab equipment and training.

“It was a pretty significant switch for my lab because we went from using standard real-time Polymerase Chain Reactions to this new method called digital droplet PCR which is more sensitive and more quantitative. That required a lot of new instrumentation to be put in my lab which was installed [on Oct. 19].”

PCR is a process that can target specific DNA molecules and amplify them for analysis and quantification. To test for the genetic material in the COVID-19 viruses, Sharp and his lab are using a newer version of PCR known as digital droplet PCR which is more sensitive than conventional PCR because it breaks up the PCR reaction into nanodroplets of oil. These nanodroplets then have a fluorescent dye that will become brighter in higher concentrations of the target genetic material. Essentially, the more COVID-19 in the sample, the brighter the oil droplets will be.

The machine can then measure that fluorescence and quantify how much viral nucleic acid was in that sample. The interpreted data can tell the lab how much of the virus is in the water; information that they then share with the state and county health departments.

Sharp’s lab and its expensive PCR machines do all of the work except actually collecting the wastewater samples. The samples are sent to Sharp from the sewage treatment plant as well as from various wastewater lift stations throughout Marquette.

Mark O’Neill, Director of Municipal Utilities for City Of Marquette, says Marquette has been sending wastewater samples to multiple labs to be tested for COVID-19, including the one at Northern. Only at Northern, however, will neighborhood lift stations be monitored for the virus as well.

“We are going to be testing here at the treatment plant like we do for Michigan State but what is unique with Northern is we are also going to go out and test individual lift stations throughout the city,” O’Neill said. “We are going to be testing those lift stations with the thought that if we have an outbreak, we may [be able to track] an outbreak to a certain lift station that serves a certain part of the city.”

Samples are collected daily at the wastewater treatment plant that are then bottled and shipped to Sharp for analysis. This analysis can be done in as little time as a day but can also take up to 48 hours.

“Once you get the wastewater in, what you have to do is separate the virus out of the wastewater, then you have to extract the nucleic acids from wastewater and then you can go and do the PCR from there. It is actually a four step process because then you have to analyze the data,” Sharp said. “In a lab that has a lot of experience with this technique, you can get the answer in about a day, but with a newer lab like us that is just starting doing this, it is probably going to take another day or so to get the data.”

Once they have the data of how much genetic material from the COVID-19 virus is in each wastewater sample, the county and state governments can use this data to determine where the next potential outbreak may be or where to focus their efforts of containment.

“What is nice with this data is it gives you an idea of how much the virus is spread in the community, because this will not only pick up the virus coming from symptomatic people but also people that are asymptomatic. The people that are asymptomatic still shed the virus in their waste so it gives you an idea on a community level of how much of the virus is actually there,” Sharp said. “We are going to be measuring a few areas around Marquette so we will have an idea of what is happening in various neighborhoods and if we see high levels, then we can sort of narrow down which buildings may be contributing to those high viral levels.”

Working on this project with Sharp are five students and a research technician, all of whom need to be trained before being able to use the new ddPCR machines.

“It is a great learning opportunity for students and myself. This is a new PCR technology for me so I get to learn something as well which I find exciting,” Sharp said. “It is going to be a really great skill set for students to acquire; having this experience using this new type of PCR. When they graduate, that is going to be a really marketable skillset to have.”

One of the students in Sharp’s lab is second year forensic biochemistry and pre-med student, Bailey Gomes. Gomes hopes to work as a pathologist after medical school where PCR technology is used almost daily.

“PCR is very commonly used in just about every lab; anything that has to do with DNA, PCR is typically used so that would be incredibly helpful,” Gomes said. “Also just being able to familiarize myself with being in a lab setting and all of the lab procedures is just very closely aligned with the career I’d like.”

Gomes and the other participants working in the lab will be trained via Zoom this week and will receive an in-person training of the ddPCR procedures the last week of October. After they are comfortable with the equipment, they will finally be able to begin testing the wastewater samples and sending their data to the health departments.

“I’m really looking forward to the experience as a whole but I’m also really looking forward to learning the new techniques,” Gomes said. “I like to say my brain is a sponge; I can never get enough new information so I’m really excited to learn these new techniques and be able to apply them in the future.”

Not only is this a great way for Marquette and the state to be able to track and better predict the spread of COVID-19, it is also providing a valuable learning experience for all those involved.

“I think this is a great opportunity for students to see public health in action,” Sharp said. “How you go from acquiring samples from the environment to testing for the virus and what happens to that data afterwards.”