A brief history of racism and the fight for racial equality at NMU

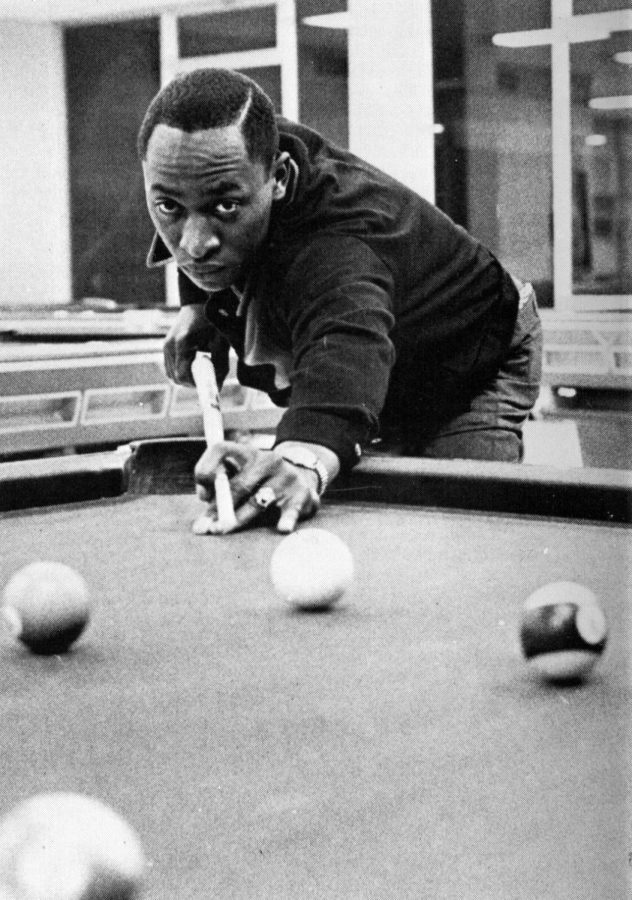

Photo courtesy of NMU Archives

FIGHTING BACK – Charles Griffis, the student whose suspension led to the sit-in in Al Niemi’s office, lines up a shot at pool. Griffis’s suspension led to a sit in protest by over 100 NMU students in 1969.

February 10, 2022

February is Black History Month and it is important to recognize the racial inequality, specifically for Black students, that has occurred globally but also at our own Northern Michigan University. The NMU Archives covered the vast history of protests and sit-ins at NMU in their student protest exhibit written in 2015 by Annika Peterson, Anne Krohn and Kelley Kanon.

Two sit-ins were prominent in the late 1960s: an important basketball game was canceled when students flooded the court in response to long-standing racial problems and over one hundred students protested in the Dean of Students Offices after the the unfair suspension of an African American student.

The first instance of organized racial protest in the U.P. took place on Dec. 9, 1968 when members of the Black Student Union walked out onto the basketball court right before an important game against the Pan-American team was about to begin and sat down, refusing to leave.

The sit-in was a reaction to the previous day when Black students David Williams, Michael Gaines and Charles Moore were denied access into Spooner Hall because the police officer on duty refused to believe they were students, even after the residence hall leader James Charmichael vouched for them.

According to the Mining Journal interview a day later with Director of Security Police Wayne Stambaugh, security police checks were more rigorous in the building at the time because Job Corps girls had recently moved in. The officer on duty claimed the students were becoming abusive so he called in more police for help who showed up with billy-clubs, though no physical aggression took place.

That following evening nearly 150 African American students marched onto the court and sat down before the game could begin. NMU President John Jamrich persuaded them to leave in return for meeting with him the following morning to discuss their concerns, but the students held their positions and forced the game to be canceled. According to spectators, the demonstration was unorganized and there were no clear demands, but Payne and Williams both told the Mining Journal reasons for the protest with demands such as including more Black culture classes and recruiting more Black faculty.

Jamrich and the protestors met the next day. Jamrich emphasized that they should be disciplined for disrupting the game but none of the students were punished and they came to many agreements: the development of a human rights commission, the development of improved procedures to better the relationships between security staff and Black students, the employment of more Black students by the university, the recruitment of more Black students and faculty and the addition of a Black history course.

Despite these agreements, racial tensions remained within NMU. Robert McClellan, assistant professor in the history department at the time, recounts the “The Case of the Marquette Six” in a 1989 interview, calling it the most prominent racial event in 1969-70.

McClellan said that in 1969, guns were prominently displayed in dorm windows after a Black man had supposedly been shot at on campus and the event at Jackson State was on people’s minds resulting in a fear among the Black community.

Around the same time, Charles Griffis, a Black student, was dating the former girlfriend of a white RA and McClellan said the RA got “sore”. Wanting to get back at Griffis, the RA caught him with a girl in his room which was against dorm rules.

Griffis was put on trial at the student judiciary for the minor infraction. McClellan said there was hostility towards Griffis when one of the white jurors claimed he would punch Griffis out if he ever showed his face again.

Griffis was suspended for his actions but he went to the Human Rights Commission because he felt like he was unfairly punished. The HRC agreed and wrote a letter to Jamrich asking him to overturn the suspension. In response, Jamrich asked the Student-Faculty Judiciary to begin an appeal trial for Griffis.

Despite the potential appeal, on Dec. 17, 1969, over 100 Black students held a sit-in within the common space of Kaye Hall from 9 a.m.- 5 p.m. When the hall closed, the protestors moved to Vice President of Student Affairs Allan Niemi’s office at the Dean of Students Offices.

One of the office windows was shattered and pieces of furniture were broken; Niemi went to investigate and was apparently held hostage by the protestors, threatening him with a two-by-two and a broom stick. However, the students claim he was never prevented from leaving.

Jamrich eventually made his way to the sit-in and was refused access by the students. McClellan said that Jamrich called the state police to come and “get these f****** n***** out of here” but he and other faculty members convinced Jamrich to negotiate with the protesters instead. Meanwhile, the Student-Faculty Judiciary announced that Griffis was found innocent at the appeal due to “insufficient evidence” of his case.

Niemi and most of the protestors left; some of the students stayed to help clean the office and argue with Jamrich that they should not be charged in court, but Jamrich felt that the sit-in was unwarranted and they should be disciplined for their behavior.

Jamrich contacted Ed Quinnell, prosecuting attorney for Marquette county, and told him of the trespassing, destruction of property and potential kidnapping committed by these students which led to an investigation.

Twenty-four students who had been identified from the protest were charged within the university. The HRC met with Jamrich and asked if he would pardon all students involved in the sit-in and he refused. During this meeting, twelve white students from the Negaunee-Ishpeming area gathered outside the office to show they supported Jamrich’s actions against the protestors.

All twenty-four students were found innocent at the trials. However, Quinnell filed charges against six students as the leaders of the protest: Vernon Smalls. Patrick Williams, David Williams, Christopher Poole, Loren Lobban and Phillip Harder resulting in the name “The Case of the Marquette Six”.

McClellan helped the students find radical attorney Kent Bourland to work full-time on the case with only the few thousand dollars the students managed to raise. The trial began April 21 and nearly 75 white students protested outside of the courthouse to show their support for the Marquette Six.

One week into the trials, the case was declared a mistrial and McClellan never found out why. The charges were never reinstigated.

These two sit-ins contribute to the vast history of protests at NMU, portraying the strength and resilience of students striving for racial equity on campus and within the community.

Northern has come a long way since guns were allowed in campus buildings and dorms were not co-ed; however, it is important to remember the instances of racial injustice that stamp the university’s history in order to move forward with further positive change and unity.