Students present medicinal plant chemistry research in California

photo courtesy of Gino Pacifico

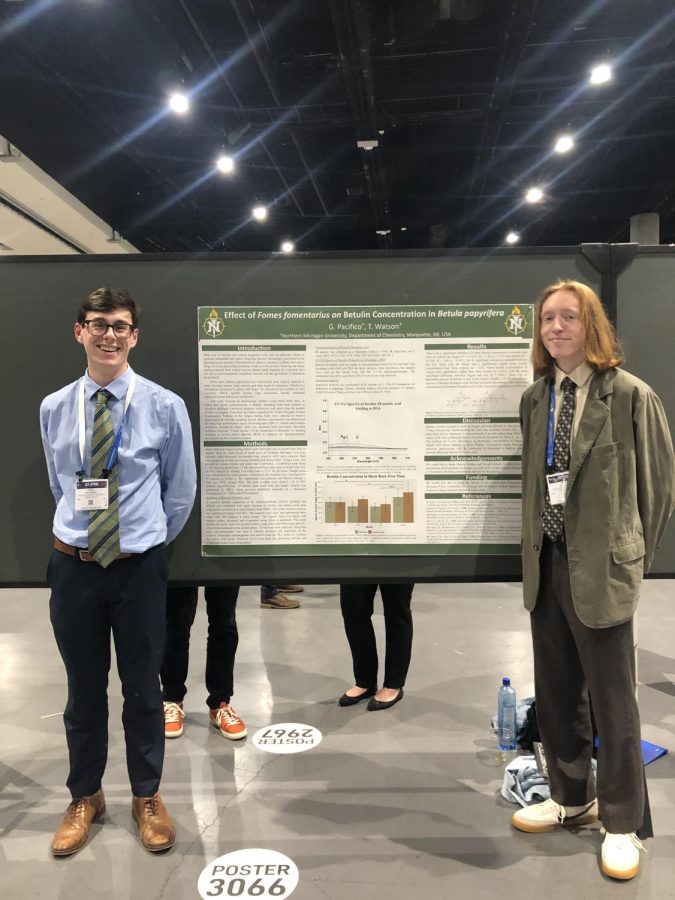

CANNABIS RESEARCH – Gino Pacifico and Tyler Watson present their research on the pharmaceutical applications of chemicals in birch bark. They were personally invited to present their research at the conference by the head of the Cellulose and Renewable Materials.

April 1, 2022

Three NMU students from the chemistry department attended the annual American Chemical Society conference last week in San Diego to present their capstone research.

The ACS conference brings together students, industry professionals and professors involved in chemistry. It provides an opportunity for chemistry students to present their research in a setting with academic individuals, where they can network with people in the industry and further their knowledge through peer and professional presentations.

From March 20 through 24, chemistry presentations on a variety of topic areas were being displayed throughout the San Diego Convention Center and offered online presentations for virtual attendees.

Tyler Watson, senior medicinal plant chemistry major, and Gino Pacifico, senior biochemistry major, presented their research on a specific terpene, betulin, found in birch bark. Terpenes are the compounds in plants that give them their scent but have also been found to have anti-cancer properties. The duo’s research was to see if betulin could be used to create medicinal drugs.

Earlier in the year, Watson and Pacifico presented their research at the local ACS students symposium and were afterward invited to present at the national conference.

“If [our research] worked out, then birch trees, and especially the waste [impact] from the paper industry, could serve as a wide, abundant, sustainable source of our compound,” Watson said.

Watson and Pacifico took samples from several birch trees from May through August and compared the concentration of betulin in each specimen. The samples were from living trees, dead trees and trees that had a tinder fungus.

“Using the bark of the tree, you are just using dead material, so you are not really maiming the tree because the tree’s outer bark will regenerate every year,” Pacifico said. “That’s why we saw the bark as a suitable source for renewable materials.”

They found that trees with tinder fungus had significantly higher betulin levels than trees without it, noting that fungus content was highest in August. The presence of betulin content and the time of year had no impact on each other.

Betulin targets human cancer cells without impacting other cells. Currently, the drug is not very water-soluble and will not dissolve in the bloodstream.

Watson and Pacifico also explored whether or not a derivative of betulin could be transferred into the bloodstream through oral intake, testing to see if the drug could be used for its anti-cancer properties. They measured how well the betulin derivative would bind to a protein called bovine serum albumin, which is similar to the protein in the bloodstream that transports drugs and lipids.

According to Watson, if the derivative binds to bovine serum better than regular betulin, then they would be showing that the derivative is more bioavailable. This means that it has a greater potential to be used as an anticancer treatment.

“Currently you can’t use betulin as a drug,” Watson said. “If you can find a way to use it as a drug, now suddenly all this waste product from the paper industry could be used for something and have more economic importance.”

They have not completed their project yet, as they are still waiting to determine the binding constant between the drug and the protein, but they are hoping to complete it soon.

“[At the conference] you either get new ideas from talks or from talking with people that have a different perspective on the research you’re doing,” Watson said. “I met some people that we are going to be able to share our information with.”

Haylee Kuehl-Weiser, senior medicinal plant chemistry major, also presented at the conference.

Kuehl-Weiser removed oil extracts from cannabis flowers grown on campus using heat and pressure. She then placed those extracts in three different environments: a dark, room-temperature space, a refrigerator and under an LED light.

“My main idea was to show when extracts are placed on display, like in a dispensary, and how that would affect the product,” Kuehl-Weiser said.

Kuehl-Weiser has always wondered what happens chemically to the last product of a certain strain when it is left on the shelves, but her results were inconclusive. Her results showed that extract contained in a room temperature environment degraded faster than the extract kept under an LED light.

“[This result] seemed weird based upon what was chemically happening in the environment,” Kuehl-Weiser said. “The refrigerated sample could have had condensation on the vial that could have caused degradation to happen at a much different rate.”

Despite her inconclusive results, Kuehl-Weiser and her research benefited greatly from attending the ACS conference.

“This conference has allowed me to figure out what went wrong,” Kuehl-Weiser said. “I was able to think of things that I never would have thought of before from my background.”