Jitte Okagbare, junior special education major and liaison for Black Student Union, was only in her first semester at NMU when she first noticed the thin blue line flag in the criminal justice department’s front window last fall.

The flag, which looks like a black and white American flag with a single blue stripe across the center, had been in that window for over 70 years, according to criminal justice department head Robert Hanson. However, it was during the Fall 2020 semester that BSU started to take notice of its presence on campus.

The thin blue line flag has been displayed by many law enforcement units in America. The blue line on the flag is said to represent the idea that police are the force that stands between law disorder, citizens and criminals. Historically, “the idea of a ‘thin blue line’ can be traced all the way back to an 1854 British battle formation, a ‘thin red line’ used during the Crimean War [which was] then popularized in art, poetry and song” according to an article by The Marshall Project.

The idea of the thin blue line being a display of pride of law enforcement is not a new one, but the symbolism of the flag has evolved as awareness and protest against police brutality has progressed.

The flag had a surge in appearance after the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, and was mainly displayed in opposition to the Black Lives Matter movement as a “blue lives matter” flag.

“I think, not only for me but for a lot of people in the Black community, the flag became a symbol of fear and division between law enforcement officers and the Black community,” Okagbare said. “I saw, in a lot of the protests that I participated in last summer, there were protesters against Black Lives Matter that would shove the blue lives matter flag in our faces and tell us that blue lives matter. So instead of seeing that flag as a representation of officers who have put their lives on the line and sacrificed a lot, it was a ‘your lives don’t matter. Cops’ lives matter more than you do’ kind of thing.”

BSU brought up the thin blue line flag at a few of their weekly meetings last fall, but the conversation never left the room. When it was brought up again this winter, Okagbare decided to reach out to Hanson about the flag and ask him to take it down. She sent him an email on Feb. 18 and soon after had arranged a phone conversation with him.

“I went into the conversation with some unfair biases and I was really angry and prepared to have a pretty strong debate about it. But that is not what ended up happening,” Okagbare said. “We ended up having a 45-minute conversation and he was explaining what the flag meant to him as an officer and I was able to explain what it meant to the Black community and he was more than willing to figure out a solution where both his field of work and the Black community could be represented.”

For Hanson, the thin blue line flag has no connection to police brutality and racism. He believes the thin blue line flag is a show of respect for officers who put their lives on the line every day, and that is why he is proud to have that flag in the department window.

“We [have the thin blue line flag] in our department as a show of respect for those people with those responsibilities that do the job right and uphold the highest principles of professionalism,” Hanson said. “A number of our graduates have gone on to distinguish themselves in this related field, and further we want to demonstrate as a department that we stand for the highest professional standards for people who go into that line of work, who go into public service.”

During their conversation, Okagbare and Hanson traded stories and personal experiences and eventually discussed possible solutions to the display of the thin blue line flag. The overall discussion was a balanced back-and-forth exchange, something Okagbare did not initially expect.

“I went to the conversation ready to verbally fight, basically and demand that this flag be taken down and try to scream. In the Black community, it always feels like we are screaming to be heard,” Okagbare said. “This conversation was an eye-opener that not everyone who has this flag is a bad person. He described to me that this flag meant to him was a way to respect officers who had fallen and was just a way to say ‘I’m a cop and I’m proud.’ It had nothing to do with the movement and had nothing to do with how it evolved … He was willing to listen to my voice without me having to badger him about it and he was willing to try and understand my perspective.”

Hanson and Okagbare continued their correspondence into the following weeks and expanded their discussions to increase diversity on campus, including ways to recruit both students and professors of color to Northern.

“Talking with Jitte [Okagbare] was a transformative experience for both of us, and that is the advantage of having a touchpoint where people of goodwill come together to solve problems or to make life better or to engage in civil discourse,” Hanson said. “With Jitte [Okagbare], we started talking about what it would mean to make things better for students of color here at Northern. That was our focus: how can we help each other to understand the concerns of other people in a respectful and civil manner.”

After about three and a half weeks of emails and phone calls, Okagbare and Hanson decided one of the ways to ensure the thin blue line flag in the criminal justice department’s window was not interpreted as discriminatory was to order a Black Lives Matter flag to display alongside it.

“Flags are symbols and symbols have a lot of power … we don’t fly [the thin blue line] flag because we want to proclaim to the world that we are racist, but if a person of color walks by our office and sees that flag and has been taught that it is a symbol of oppression, that it is something to be fought against, and we are looking at it as a freedom of speech,” Hanson said. “By showing [both] flags, we are affirming our commitment to free speech on both sides and the commitment to respectful dialogue between people.”

Even after the Black Lives Matter flag was ordered, Hanson and Okagbare continued to talk and began to connect BSU with the Criminal Justice Association.

The two student organizations met for the first time on March 12 and talked about what the thin blue line flag meant to each of them as individuals and any personal concerns they had surrounding the flag. The meeting was also a place where they could get to know each other and have broader conversations.

“The first [meeting] was really just about getting to know each other, getting to know them, why they chose criminal justice, how they feel about their major, what’s going on in the world and stuff like that,” D’Mario Duckett, junior medicinal plant chemistry major and president of BSU, said.

The meetings also touched on changes to police academy training and potential ways that the barrier between the police and community could be diminished, Amber Liberacki, senior criminal justice major and president of Criminal Justice Association, said.

Not only were the meetings between the two groups beneficial for them to get to know each other and hear multiple perspectives, but they created a space for building potential solutions as well.

“Something that stands out to me the most about these conversations, aside from the content itself, is the amount of respect that was shown between the two groups sharing their opinions,” Liberacki said. “I am proud that both groups went into our first meeting with an open mind and from that, I thought that all of the discussions had a better outcome.”

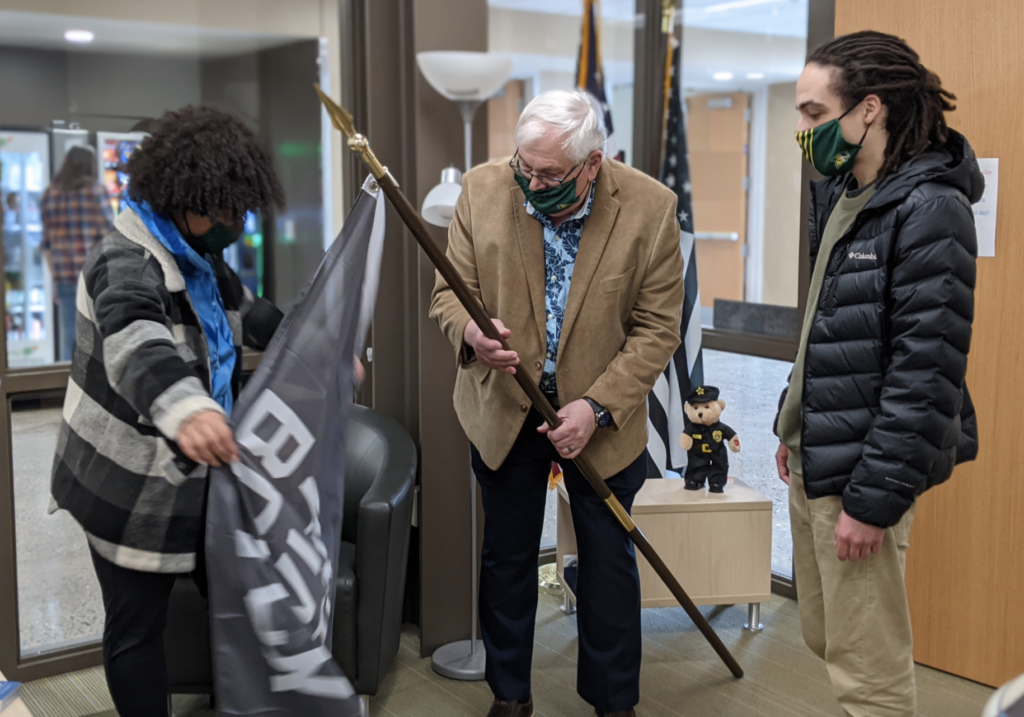

As BSU and CJA continued to build their new relationship, the Black Lives Matter flag that had been ordered for the criminal justice department window finally arrived on April 9.

Okagbare, Duckett and Hanson all worked together to assemble the flag and display it in the front window, right in between the American flag and thin blue line flag.

“There were definitely moments when I thought it wasn’t going to happen. I didn’t think that there would be enough time for us to get the flag ordered and I thought it was just going to be pacifying from [Hanson’s] staff … but that wasn’t the case,” Okagbare said. “He was so kind and so willing and so eager to move forward with this plan and the thing that actually took the longest was just the flag getting here … him participating and helping us put it up and watching him put it in the window in between the blue lives matter flag and between the American flag was just a real tear-jerker, especially with everything the Black community has gone through these past couple years. It was just awesome to see. It was very exciting.”

The addition of the flag was a moving moment for all those involved.

“It gave me chills because I saw in that moment that there is really hope for learning opportunities to take place,” Hanson said. “Unfortunately I think there are people in responsible positions as teachers, as professors, that are much more interested in radicalizing students than teaching them how to be respectful and civil in any disagreements that come up … For me, it was the triumph of goodwill over antagonism. And what a powerful moment.”

For Duckett, the addition of the Black Lives Matter flag was important, but he still believes there is much more work to be done.

“We put up the Black Lives Matter flag but personally, the Black Lives Matter movement, it doesn’t mean that much to me personally,” Duckett said. “But blue lives matter, that is clear opposition to me so I would have rather them take down the blue lives matter flag, but this is the compromise that we came to.”

Looking into the future, BSU, CJA and the criminal justice department are hoping to continue working together, both in and outside the classroom. They are discussing involving BSU in some of the criminal justice curriculum for greater input and potentially scenario training, as well as organizing events for the wider community to participate in.

“The students have made this into something real and now we are talking about bringing in a speaker in the fall so we can address these broader societal issues,” Hanson said. “They are doing things together, they are having dialogue [and] are starting to make friends or at least acquaintances.”

BSU and CJA plan on meeting and organizing events next semester and for the semesters that follow. They hope the two clubs will continue to have discussions and build a relationship, even after the current leadership and members have graduated.

“CJA and BSU now have a stronger relationship that is built purely on the groups being honest with each other and respecting the voices of each individual that is involved,” Liberacki said. “I hope that these two groups continue to meet for years to come and hopefully influence other colleges and universities to join in.”

The meetings between BSU and CJA are important steps in the process of making Northern and Marquette more inclusive towards the Black community.

“I think that the conversations we have had have been so beneficial and we built a new relationship with the Criminal Justice Association and the department as a whole,” Okagbare said. “I don’t think our work is done yet, but it is these conversations that get the ball rolling.”

Students interested in joining BSU can visit their website or email them at nmu.bsu@gmail.com. Students interested in joining the Criminal Justice Association can join their Facebook or contact them at aliberac@nmu.edu.