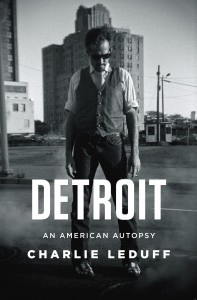

“Detroit: An American Autopsy” by Charlie LeDuff is exactly that, an autopsy. It’s a dissection of Detroit as if it were a murder victim. It’s a reporter’s journey through a crumbling city attempting to determine the cause of death. LeDuff, a former reporter for The New York Times, moves back to Detroit to work for the The Detroit News and captures the city in one of its most devastating eras.

LeDuff begins his book when he starts working at the News in March 2008. He illustrates the devastation of Detroit as a framework for the entire storyline. The city had seen the largest population decline of the past 60 years, becoming the only city to rise above a population of one million only to fall below that, to 713,777 people. Urban decay has dominated the landscape with massive historical buildings, like the Packard Automotive Plant and Michigan Central Station, becoming abandoned and left to the homeless and the looters.

As someone who’s spent most of my life in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, I didn’t know much about Detroit, past or present, before I read the book.

LeDuff weaves the history of Detroit, which at one time was the richest city in America, into a gripping journalistic adventure complete with villains, damsels and heroes.

The book is separated into three parts: Fire, Ice and From the Ashes.

The first section focuses mainly on his determined spirit to investigate the wrongs that have been overlooked.

LeDuff blatantly calls out the corrupt government officials of the city, like former mayor Kwame Kilpatrick and former city councilwoman Monica Conyers, as the evil-doers. He contrasts them by using the everyday people of Detroit as the good guys. These “Average Joes” get more than their 15 minutes of fame as LeDuff uses them to show a glimmer of hope for the city’s comeback.

The Detroit firefighters play a large role in the book as LeDuff portrays them as the unrelenting loyalists to the city. They refuse to let it burn even when arson becomes an everyday occurrence.

LeDuff’s raw description of characters colors the storyline. He doesn’t censor his inner monologue, using descriptors like “streetwalker,” “balls-out” and “overfed buffoon” and there is no shortage of similes and metaphors.

Ice is a continuation of the first section, first centering on a dead man LeDuff finds frozen in ice at the bottom of an elevator shaft in an abandoned warehouse. As a journalist, something I appreciated from this section was his artful explanation of why reporters write about the bad and the ugly more often than the good.

After writing a story about the frozen man, LeDuff received criticism from a segment of the Detroit community saying he was “focusing on the negative in a city with so much good.” His response is priceless.

“It was a fair point. There are plenty of good people in Detroit,” LeDuff said. “But these things are not supposed to be news. These things are supposed to be normal. And when normal things become the news, the abnormal becomes the norm. And when that happens, you might as well put a fork in it.”

In the last section of the book, From the Ashes, LeDuff seems to lose control of the story altogether, but almost purposefully so in order to show how he lost control of his emotions.

He had become so absorbed in Detroit that he could no longer separate himself from it and therefore, his sanity spiraled out of control just as Detroit did.

He dives into a long history of his family tree after he meets a distant aunt. Throughout the final section, this history seems to haunt his present. LeDuff ultimately illustrates the complete havoc that consumed Detroit as an eerie foreshadowing for the rest of America if government corruption continues.

He represents the press’ function as the fourth estate and assumes responsibility to unveil what went wrong in the city. In the end, he believes the good people left in Detroit who survived this era may be the ones to lead the nation out of the shadows and into prosperity again.

“I believe Detroit is America’s city,” LeDuff said. “It was the vanguard of our way up, just as it is the vanguard of our way down. And one hopes the vanguard of our way up again. Detroit is Pax Americana. The birthplace of mass production, the cement road, the refrigerator, frozen peas, high-paid blue-collar jobs, home ownership and credit on a mass scale. America’s way of life was built here.”