Creative success isn’t some sort of white rhino. Andy Warhol didn’t do much that you or I can’t do ourselves. He, like other successful artists, came up with an idea he thought was good enough, and then worked himself down to the bone to produce and sell

that idea.

The Campbell’s Soup pieces, the Elvis pieces, the banana stuff; it’s hardly art, some say. Barely original. But Warhol created whatever art he wanted and somehow made a pile of money—he took his idea a step further than most of us do and executed it. Warhol was, and is, a household name.

We sometimes roll our eyes at contemporary art. “Damn, I could’ve done that,” you say as you look at Piet Mondrian’s “Composition with Blue, Red, Yellow, and Black.”

I recently saw it in person at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and yes, you certainly could have done it. It’s a normal canvas, normal paint, by a normal guy.

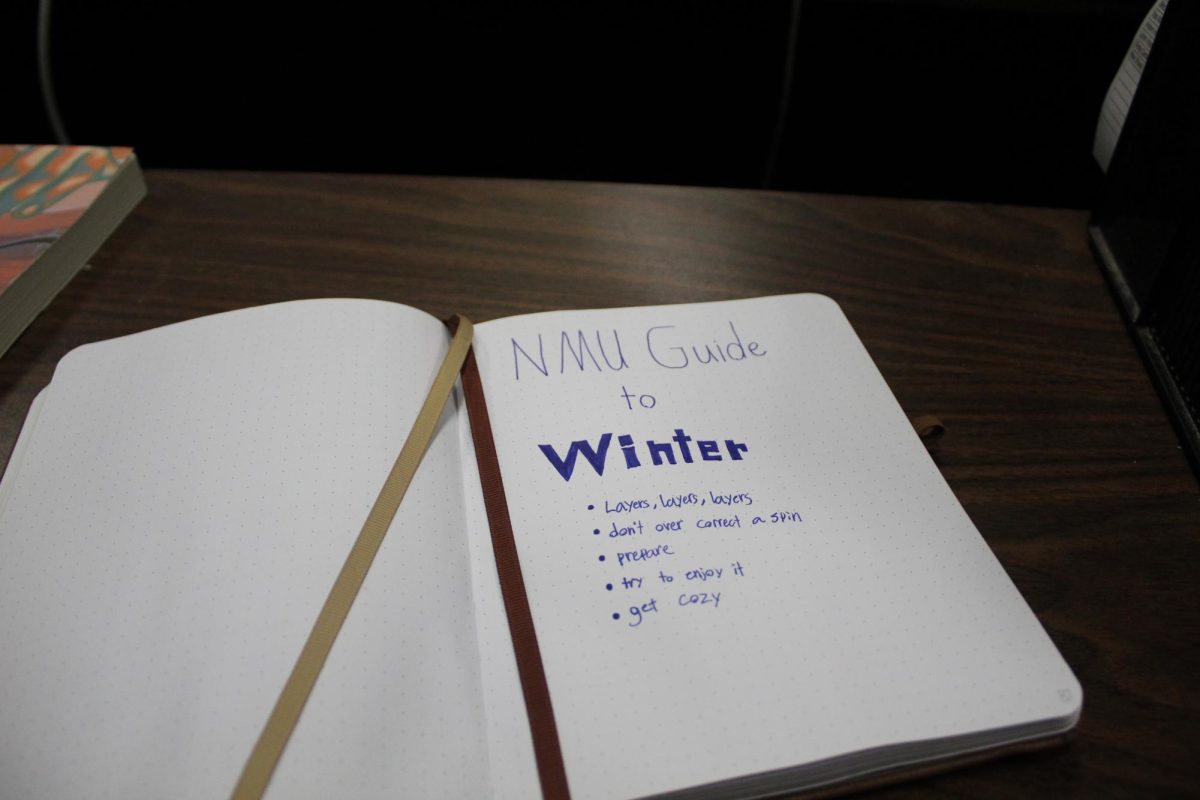

But perhaps a creative image comes to you while you’re daydreaming; the first chapter of a novel, or a scene you’d like to paint or a specific concept you want to photograph.Perhaps you even go so far as to write it down, you know,

for later.

But the thing is, we don’t execute it. If we fully executed it, our stuff could be on display in the MIA next to Mondrian, and not just hanging limp, tacked to the drywall.

“Mad Men,” a television drama on AMC, draws inspiration from the works and personalities of the 1960s advertising industry; protagonist Don Draper is loosely based on George Lois, one of the original “mad men.”

Lois took the idea of executing his creative plans to a whole new level, once even threatening suicide if a client wouldn’t take his advice seriously. This man is (he claims) responsible for conceiving the “I want my MTV” ad campaign, the swift rise of Tommy Hilfiger and designing Esquire covers during the 1960s and ’70s. He was a creative force behind the visuals of pop culture in the second half of the 20th century. Calvin Klein knew who George Lois was. Andy Warhol knew.

Lois’ advice: your idea, your criticism, your theories aren’t worth a thing if you don’t produce work.

His book, “Damn Good Advice (for people with talent!),” is a manifesto of what it took for him to gain ground in the creative industry. The proverbs and parables contained within the book apply to designers, writers, artists, salespeople—really, anyone who’s ever tried to get a job in the creative industry before.

One of Lois’ best quotes from this book is the one I think is most broadly applicable to artists selling their own work in any instance: “I don’t care how talented you are. If you’re the kind of creative person who gets your best work produced, justifying and selling your work (to those around you, to your boss, to your client, to lawyers, to TV copy clearance, etc.) is what separates the sometimes good creative thinker from the consistently great one.”

And by great, he means productive. Successful. Recognized. Financially secure. He means that it isn’t enough to write a great short story or compose a great song; get it published, for crying out loud. Make some royalties. Cover your expenses, get some exposure, see something you created on the shelves of a bookstore or in a gallery.

Any idiot can splatter paint and be a “starving artist,” worrying about making rent and so on. But can you commit all the way, produce work worth selling, and then go sell it to buy food and shelter? If not, professional art may not be for you.

I’m not saying I’m so good, myself. I still have bigger aspirations than I have work ethic. But I’m trying, and trying desperately, to make those two lines intersect—as all of us should.