As NMU enters the third week of the winter semester and approaches one year of dealing with the pandemic, certain sights once considered alien is now familiar. Face masks, social distancing and distance learning for the entire campus were all but foreign concepts just one year ago. Now, with a vaccine offering some hope for the future, students may wonder when this will all be over.

The unpredictability of the virus makes it difficult to pinpoint an end to the pandemic. Josh Sharp, an associate professor of biology, says this coronavirus has surprised him.

“Coronaviruses are incredibly common in the environment,” Sharp said. “Usually they cause symptoms very similar to the common cold.”

Unlike past coronaviruses, symptoms of the current virus can have varying levels of severity. That inconsistency, coupled with the virus’s airborne spread, is a recipe for a pandemic.

“Different viruses pose different challenges,” Sharp said. “For example, polio has different challenges because it spreads through water and food contamination, as opposed to COVID-19, which is respiratory spread.”

Sharp compares the spread of a coronavirus to that of influenza because both of them spread via airborne transmission. Everyone breathes, so airborne viruses have a particularly effective means of moving from one person to another.

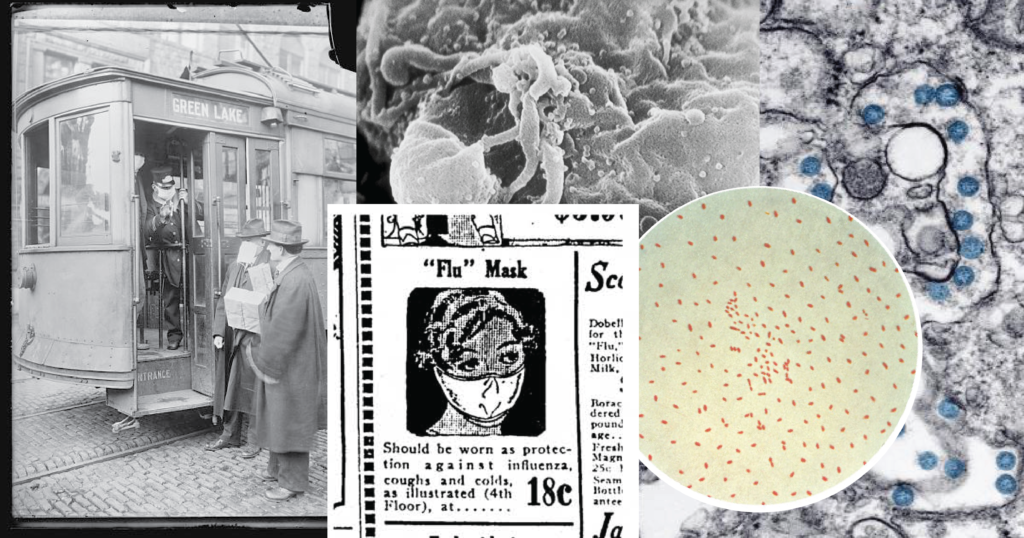

COVID-19 may seem like a new threat facing the Upper Peninsula. However, the situation today bears some striking similarities to another pandemic that hit the U.P. and the university over 100 years ago.

The Spanish flu began in Kansas in March of 1918 where it claimed the lives of 48 men stationed at Fort Riley. It is theorized that the virus was later spread globally when soldiers from Fort Riley went away to war. The resultant pandemic caused over 20 million deaths worldwide.

Influenza arrived in Michigan in September 1918. The following month, the State Board of Health made the following statement (quoted in a 1998 edition of Harlow’s Wooden Man, a quarterly journal from the Marquette Historical Society):

“The disease disseminated directly from one person to another by coughing, sneezing or violent talking directly into another’s face. It is a crowd disease and the rapidity of its dissemination is inversely in proportion to the distance between individuals. Talk over your shoulder and into the ear of the listener. When you must sneeze, protect others by placing your handkerchief over your mouth and nose. Influenza, in and of itself, is not a highly fatal disease. Its great danger lies in being a starter for pneumonia. You will not get influenza unless someone coughs, sneezes or spits in your face.”

As the disease continued to spread, the citizens of the Upper Peninsula took greater precautions to protect themselves and others. Marquette health officer Dr. Charles Drury encouraged the widespread use of gauze masks. Employees such as post office workers, store clerks and garbage men wore them, as well as some everyday citizens. Ishpeming also embraced the use of masks and provided masks to citizens as needed.

Ishpeming led the way for the closure of public buildings during the pandemic. Public assembly was banned in all places, including schools. Marquette soon followed, closing all public buildings and schools. NMU, then known as the Northern State Normal School, closed as well.

Although Northern Normal wasn’t open for classes, one of its buildings was used to isolate infected residents, similar to how Spalding Hall has been used recently.

Each case of influenza in Marquette was marked with a pin on a map of the city. Efforts were made to track and contain the virus. Anyone with symptoms was to be isolated immediately. In addition to the measures taken by cities, statewide restrictions were also put in place, according to the Marquette Historical Society.

“On Oct. 22, the Governor’s decree was published in the Daily Mining Journal in which he officially banned all public assemblage,” the article said. “In Negaunee, gatherings of two or more persons in pool halls, saloons and confectionery stands were prohibited.”

Negaunee managed to avoid influenza altogether until November. A resident named Otto Korkonen assumed the flu epidemic was a joke. He left town to visit Maple Ridge, Michigan, where he eventually contracted influenza and brought it home with him.

For Michigan as a whole, the ban on public gatherings was lifted on Christmas Day, 1918. Marquette, Negaunee and Ishpeming maintained the longest bans in the country.

On Jan. 6, 1919, public schools reopened Northern Normal among them. Influenza cases spiked twice in the following months. Both times, the bans were reinstated until the virus was back under control.

Over a century later, the Upper Peninsula finds itself in a situation similar to the Spanish flu. Much has changed in the last 100 years, but maybe there is something to be learned from history.

Junior history major Emily Tinder is the senior student assistant at the university’s archives. She became interested in the Spanish flu pandemic when she found that it coincided with the women’s suffrage movement, which was active in Marquette at the time. She approves of the way Northern Normal responded to the 1918 pandemic.

“It was a smaller school, and obviously they didn’t have the remote learning like we’ve had,” Tinder said. “But they took it seriously. It was something that concerned the students, and they took their health seriously.”

With all of the similarities between the Spanish flu and COVID-19, people may wonder if COVID-19 will also see a resurgence. Some students fear it might. Bailey Gomes is a senior majoring in forensic biochemistry pre-med and is taking a class in medical microbiology this semester.

“Once we think it’s over, there will most likely be a large spike of everyone going out,” Gomes said. “It might push us back as far as progress goes.”

The precautions taken by NMU are only part of the solution to the current problem. Individuals have the power to make choices that will help or hinder the fight against the pandemic. Gomes shares a sentiment that would have sounded familiar back in 1918.

“All of us are sick of staying home,” Gomes said. “All of us are sick of not seeing our friends and our family, but it’s something that is necessary.”

If the history books are any indication, she may very well be right.

Editor’s Note: The student quoted in this piece, Emily Tinder, is also chair of The North Wind Board of Directors.