Phyllis Michael Wong gives a voice to the Gossard Girls

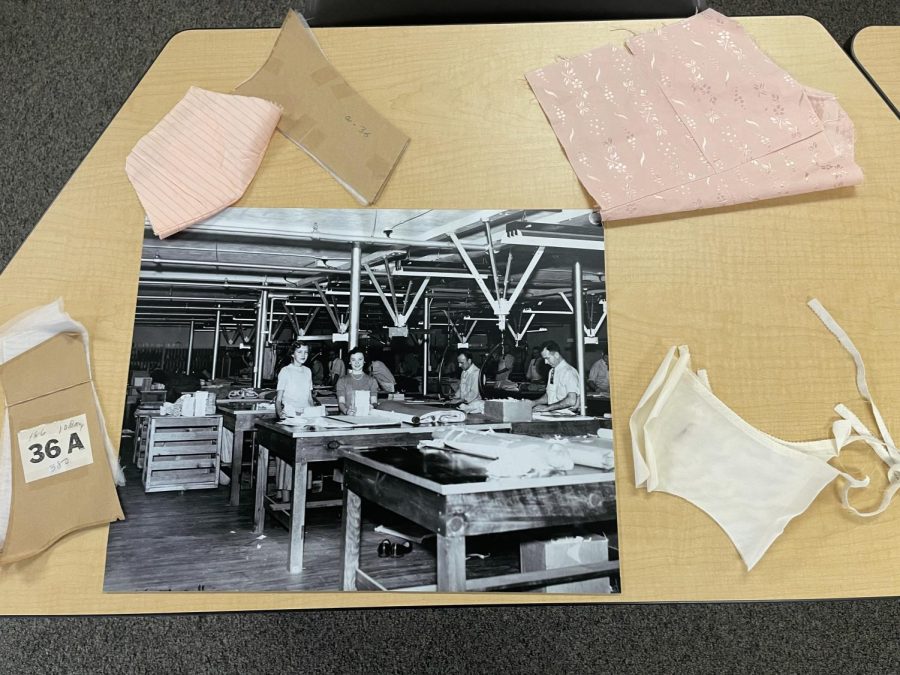

BRAS, CORSETS, GIRDLES OH MY! – Phyllis Michael Wong displays authentic fabrics and outlines that were used by the Gossard Girls during their production of women’s undergarments. The Gossard Girls kept the town of Ishpeming, Michigan economically well for over 50 years while pushing the societal boundaries that limited union and labor rights for women at the time.

April 18, 2022

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan has been considered a special place for Phyllis Michael Wong since she moved up here in 2004. While the beautiful views along the Lake Superior Bay and the unique culture are alluring enough for most, Wong, former first lady of NMU, became “hooked” on the stories that floated about the U.P. More specifically, the history of the Gossard Girls of Ishpeming, Michigan.

“I was lucky, just lucky, to listen to and hear stories from women in Ishpeming who worked in a women’s undergarment company,” Wong said. “They were piece-workers in the Gossard factory, and their stories were fascinating. They were very proud of what they did.”

This past Thursday, the Lydia M. Olsen Library hosted Wong, historian and educator, for a presentation of her non-fiction book We Kept Our Towns Going: The Gossard Girls of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Interested individuals gathered as Wong discussed her discovery of the Gossard Girls, her interviews with the piece-workers and key events in the factory’s history.

With what began as a joint research project, Wong originally set out to document the story of Geraldine Gordon Defant, a former Marquette County commissioner who made a difference in her community. As Wong began interviewing women to acquire information about Geraldine, however, she became fascinated with a building she knew nothing about, the old Gossard Factory, and the women who kept it afloat.

“I wanted to find out who are these voices, who are these people, who are these girls,” Wong said. “The history of the Gossard girls demonstrated that jobs empower workers, and these jobs empowered many dozens and dozens of women.”

Using an oral history approach, Wong interviewed countless women, recorded their stories and wove them together in respect to a timeline when creating this book. Relying on individual stories to paint an authentic picture, however, has long been rejected within the historical realm.

“It has taken a long time for the history world to accept oral history,” Dan Truckey, Director of the Beaumier U.P. Heritage Center, said. “Scholars and historians felt dubious about oral history. They felt that it was the voice of commoners who wouldn’t understand or appreciate what they were seeing. But [oral history] is a process that if done well can create a body of material and perspectives that are really important.”

Wong understood the importance of giving people a voice, especially women.

“You never know what someone is thinking unless you give them a voice,” Wong said. “When you give them a voice, really give them a voice, and you are listening, what will you hear?”

The H.W. Gossard Factory opened in 1920, a year defined by the advancement of women’s rights in terms of voting. The factory operated for 56 years, reaching its height in the 1940s when it operated as the second-largest business in Ishpeming. At that time, nearly 600 workers were employed at the Gossard, most of whom were women, making it the largest women-dominated industry in the U.P.

“Most of [the women], 85 to 90%, told me they were piece-workers who earned their money by doing one part of the operation in assembling a corset or a bra,” Wong said. “The women needed to work as fast as they could because piece-workers made money [by the garment]. Workers only got paid for garments that passed inspection.”

The work environment at the Gossard Factory was extremely intense. While the women would laugh, share wisdom and tell jokes as they sat side-by-side on the seaming shaft, they were there to work and make money. The assembly of undergarments became a competition for the girls, trying to be better and faster than the next in order to generate the most profit.

As Wong continued to interview more and more Gossard Girls, she began to notice a common characteristic that was attributable to most of them: their willingness to sacrifice. Many of the Gossard Girls shared a similar background, concealing their real age and quitting school to work and support their families during economic hardships.

Yet despite the competitive nature of the job they were tasked to complete, the Gossard Girls all loved and supported each other. When the 16-week Gossard Factory strike began in 1949, the comradery that silently existed within the factory was able to see the light. One woman in particular, who had to quit work due to the birth of her son, continued to support the Gossard Girls and their union goals despite her lack of employment.

“During the period of the strike, this woman lived near the factory where all of the strikers and picketers were. They asked her ‘can we use your garage for in between [to rest]’ and she said ‘of course you can,’” Wong said. “In appreciation for what she did for the picketers they bought her a baby buggy for her newest child.”

The Gossard Factory strike proved itself to be a monumental movement for women’s work rights and union rights in the Upper Peninsula.

“The Gossard strike was the first women-led strike in the U.P. dealing with unfair labor practices. These were women on the line for other women,” Wong said. “They wanted a more equitable environment and more importantly a union shop, which was the biggest issue.”

With support from the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, the Gossard Girls were able to secure their union shop. Despite all of the trials and tribulations that accompanied being a factory worker, the women were incredibly thankful for the experience that the Gossard Factory provided them.

“The work at the Gossard gave them agency. Not just for making money and doing something for the families and the community, but for themselves,” Wong said. “They became stronger, more confident women.”

While the Gossard Factory permanently shut its doors in 1976, the legacy of the women who worked within the walls continues to permeate throughout the U.P. These women, who from a cultural standpoint were not supposed to be working, acted as the economic support system not only for their household but for the local community as well.

“If you study the 60s and 70s, you will learn about the women’s movement. [The Gossard Girls] were women who were doing this much before then,” Wong said. “That town was thriving. [The Gossard Girls] would earn money and then spend it in town. They did that and they kept their towns going.”