The Marji Gesik: The Bike Race Whose Name Means ‘Bad Day’

Photo courtesy of Rob Meendering

OVERCOMING OBSTACLES – Scott Tencate navigates a rock garden.

September 27, 2022

The Marji Gesick, sometimes referred to as the country’s toughest 100-mile race, took place this weekend for its sixth and most brutal year ever. Mountain bikers and runners traveled from all over the country to test their skills, and more so their grit, against challenging trails and themselves.

Marji Gesick, which quite literally translates to “bad day” in the Ojibwe language, traverses on single track through Marquette, Negaunee and Ishpeming.

“We intentionally chose that route because we know it is all uphill. We take the best of the worst and we put it into the route,” said race coordinator Todd Poquette.

The race is sponsored and hosted by the 906 Adventure Team, a non-profit organization, whose mission is to ‘empower people to be the best versions of themselves through outdoor adventure.’ Besides putting on races, they also run a youth bike club program that runs in seven communities, in three different states.

With 666 spots open for registration, the race is made to be hellish. In fact, that seems to be the draw to participate for most people: the challenge, the pain, the fight.

“It’s hard to put into words why it’s such a special race. It’s challenging yet beautiful, fulfilling yet intimidating, inviting and humbling all at the same time, and will keep calling you back,” said Jenny Scott, a six-time racer.

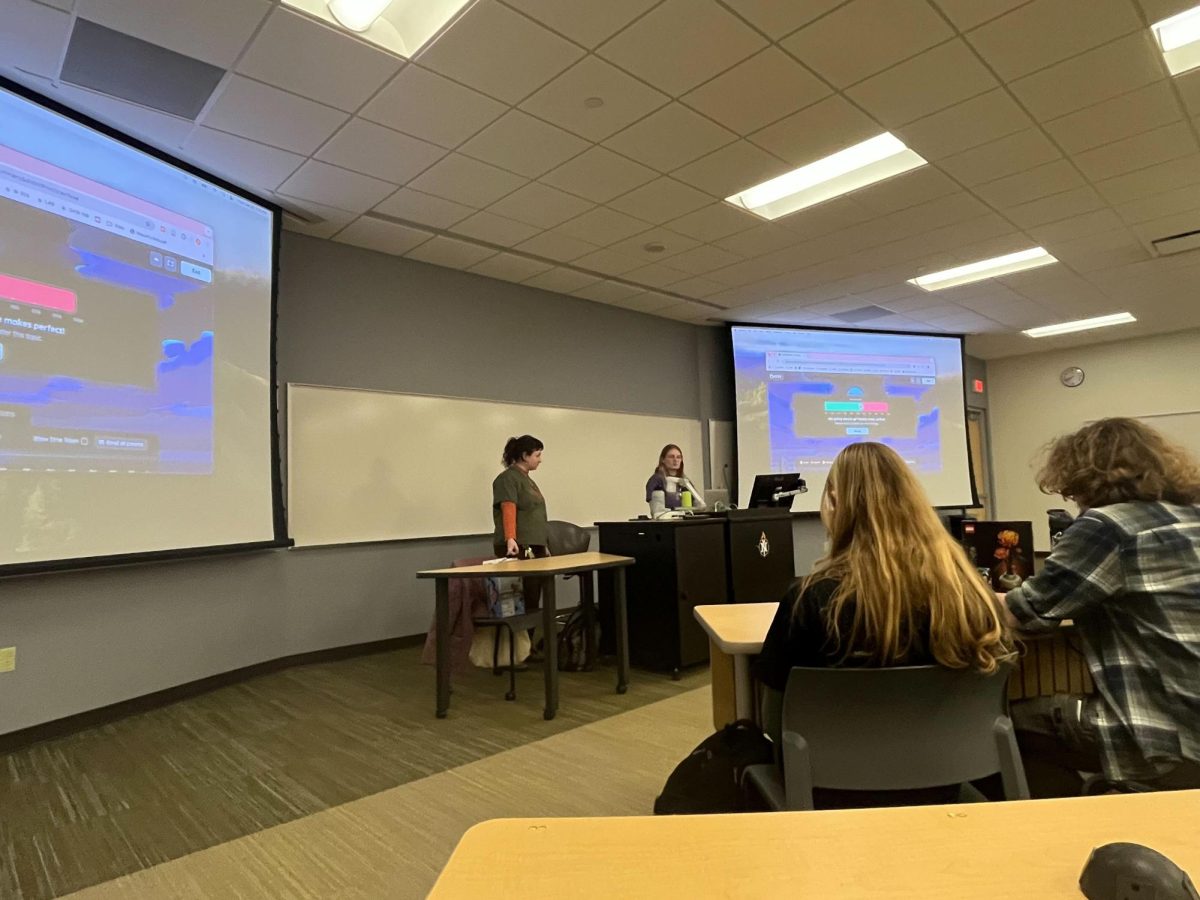

The race commenced at 7:30 a.m. on Sept. 16 for runners and Sept. 17 for bikers at the Forestville Trailhead. Heavy metal music blared through the trees as the sun rose over the horizon. Hundreds of bikes scattered the ground, guarded by stormtroopers and a man with blue hair atop an old school motorcycle.

Bikers lined up behind the starting line, seemingly excited for the grueling hours – or in some cases days – to come. A firework exploded overhead, and they were off.

The first challenge faced was a .5 mile run in bike cleats to pick up their bikes and start the 100 miles. Twenty miles later, they would pass their first checkpoint, before continuing on to five more checkpoints down the line.

Signs mark the route stating the names of the race coordinators and to blame them for the misery faced that was indeed planned.

“It means all kinds of different things to each racer. Some do it for personal glory, to test what they’re capable of, others race in memory of friends or family no longer here, some try to buckle, others just want to finish, or go further than they did the time before,” Scott said.

It was in those moments where racers needed to take a hard look at themselves and question whether they could keep going. Quitting was an unfavorable option, especially due to the fact that #QUITTER would be posted next to their name, something no one wants to be. Forty-seven percent of people who participated didn’t finish the race, however most lingered to cheer on the rest of the competitors on course and at the finish.

“When you pin a large group of people against a common obstacle, it has a way of bringing them together. Through the process of bringing people together they start to realize that they are in fact capable of a lot of the things that they thought they weren’t,” Poquette said.

Proceeds from race registration go towards the 906 team who in turn gives the majority back to trail building organizations, mainly RAMBA and the NTN Trails.

Check out 906adventureteam.org for information regarding 906’s other events, more of their story and how to get involved.