Professor Martin Reinhardt stormed out of his Texas high school when he was 15 years old and never went back. He could not see a reason to continue his education in an oppressive and conservative environment, so after getting sent home on a dress code violation, he left for good.

Despite dropping out of high school at 15, Reinhardt became the first person in his family to graduate with a Ph.D., helped create and develop Native American curriculum around the country and is now retiring from NMU after 15 years of teaching.

Reinhardt is originally from Baawiting or Sault Ste. Marie. He is a citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and is of Garden River First Nation ancestry. Despite these connections to the North Woods, Reinhardt and his family moved to Texas when he was 11. After leaving high school as a teenager, he eventually followed his brother into the Army.

“I had to really think about what I was going to do with my life at that point in time,” Reinhardt said. “I spent about a year working odd jobs, and then my brother woke me up and … he said, ‘Hey, can you take me up to go see the recruiter? I want to go check out the Army.’ …. While he was in there, I got bored sitting in the car, and I went in to see what was keeping him. The recruiter got me and recruited me into the Army.”

Reinhardt entered the Army when he was 17 and spent the next four years as a wheeled-vehicle mechanic. While he was in basic training, Reinhardt completed his GED and eventually started to take college courses.

“That was a big deal for me … to be self-determined in that way,” Reinhardt said of continuing his education. “Once I got back from the military and found out that you could learn about Indian stuff, I was just so turned on … and I’ve never looked back.”

However, Reinhardt found some of his most important teachers outside of his college classes. When he was 21 years old, Reinhardt met Nimishoomis Dan Pine Sr., an elder from Garden River First Nation.

“He was a traditional medicine person,” Reinhardt said. “I like to say he was much more medicine than he was man at the time … I met him and I was just enamored by him, and I wanted to learn from him.”

Pine called upon Reinhardt to join six other people in a fast upon the shores of Echo Lake during the two years that Reinhardt knew him. During that fast, Reinhardt became more closely connected with the seven grandfather traditions, medicine wheel teachings and other knowledge he considers fundamental to his traditional education as Anishinaabe.

One teaching from Pine that stood out to Reinhardt in particular was the saying that “there are many paths to the center of a circle.”

“It seems simple, very simple, but I can’t tell you how that has shaped my thinking in relation to our world around us, [and] being able to relate to other people,” Reinhardt said. “As a representative of the Crane Clan, and trying to think of how do I use these gifts that I’ve received, both traditional gifts and through the Western education system, for people?”

Reinhardt carried that knowledge with him as he continued to pursue his collegiate education in areas such as sociology, Native American studies and educational leadership. He attended Lansing Community College, Lake Superior State University and Central Michigan University for his associate’s, bachelor’s and master’s degree, respectively.

At Lake Superior State University, he met his wife, Tina, in a Native American studies course and he knew it was meant to be. After many different positions in academia around Michigan, Reinhardt decided to pursue his Ph.D. in educational leadership at Pennsylvania State University in their American Indian Leadership Program.

With the completion of his Ph.D. program in 2004, Reinhardt became the first person in his family to have a doctoral degree.

“My grandmother was still alive when I completed my Ph.D. She was probably the toughest person that I presented to after I completed it,” Reinhardt said. “She asked me very pointedly, ‘what does this have to do with us as Anishinaabe and Ojibwe people and our hunting and fishing rights?’ And wow, that’s a hard question to answer, but what a good challenge for me to stay grounded in our reality and not to speak that Western academic voice, but to speak in traditional Anishinaabe voice. That was a very, very important lesson for me.”

Reinhardt made sure to stay grounded in his traditional knowledge and voice when he applied for the director position at the Center for Native American Studies (CNAS) at NMU. He officially started the role in July 2001 and brought with him ideas and a passion for Indigenous rights.

Shortly after his term started, the events of 9/11 shocked the nation and Reinhardt’s own family. The tragedy also inspired Reinhardt and others in the CNAS to establish a fire site on campus where Indigenous students, faculty, staff and community members could gather and pray in the ways they needed to.

“It was clear to us after dealing with 9/11 when they said that people should find a place on campus to pray their way, we found that we didn’t have a place on campus to pray our way,” Reinhardt said. “We wanted a fire site on campus, and we finally got our wish. It was a negotiated outcome with campus public safety facilities … and that was a very big win for us as far as Indigenous rights on campus. It’s one of the few that existed at the time on any public university campus.”

The fire site was established in 2003 in the woods outside of Whitman Hall and remains an important gathering place today.

Reinhardt also helped start the First Nations Food Taster at NMU, a fundraiser typically hosted by the Native American Student Association (NASA) where the campus community partakes in a meal of Indigenous foods.

In 2005, Reinhardt left his CNAS director position to write Native American studies curriculum for an online K-12 course in Arizona. After a year in Arizona, Reinhardt realized that relationships and community were more central to his values than working at a for-profit organization and he made his way back to the North Woods with his family.

He found work in various academic settings in Michigan and Wisconsin for a few years, before applying for an open professor position at the CNAS in 2010. He has been a fixture at NMU ever since, teaching over 13 classes, serving on multiple master’s and doctoral committees and helping expand the Native American studies curriculum.

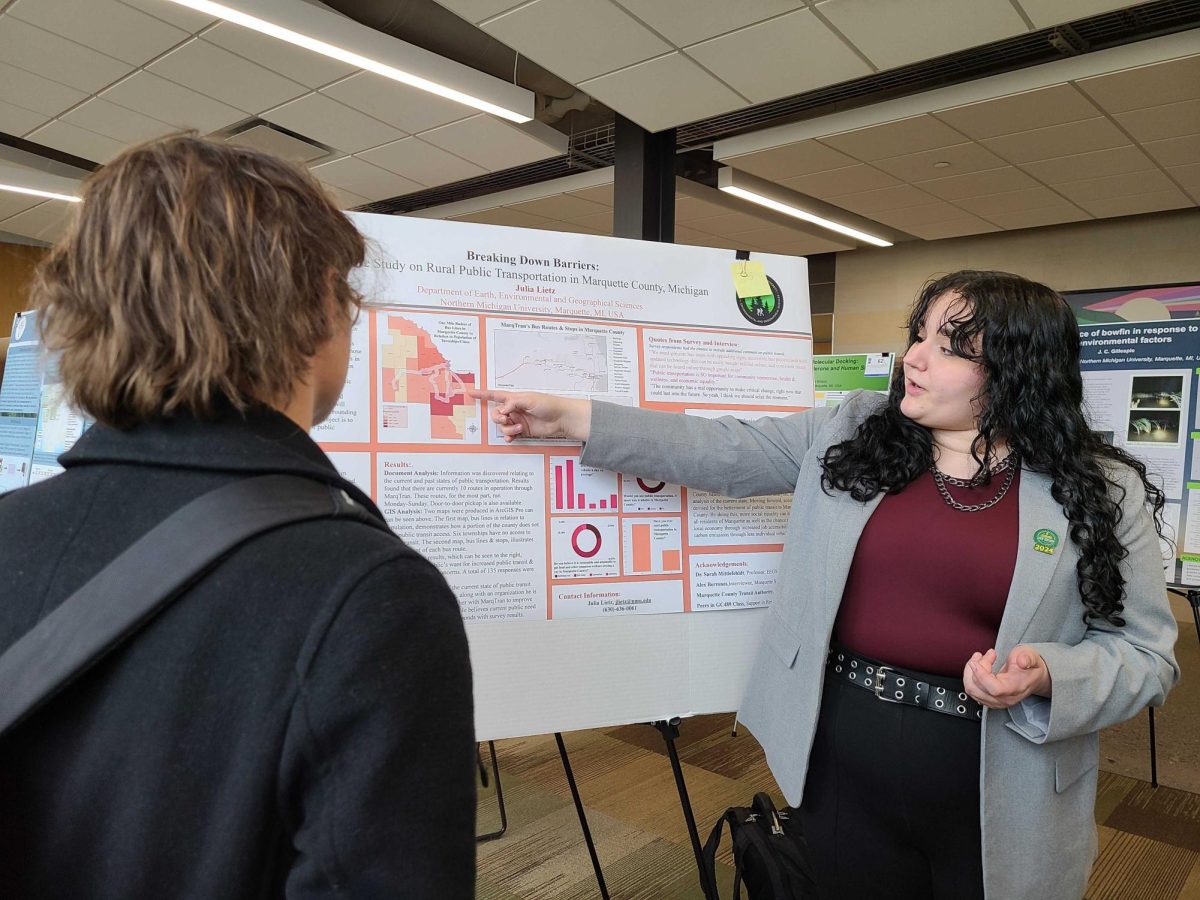

One of his favorite classes to teach has been the NAS 488 class, or Native American Community Engagement. The class acts as the capstone for the Native American Studies (NAS) major and requires students to complete community service learning projects that are generated by the community’s needs. Throughout the years, they have completed projects such as developing community gardens, making a proposal for an Indigenous biodome, working with local Native American education programs and searching the archives at NMU for documents on Native American historical relations.

“The projects are generated by the Native community; they’re not generated by the students. That’s really important to me,” Reinhardt said. “I think it’s probably the most decolonized approach of all my classes. We use a medicine wheel logic model for selecting, planning, implementing and reflecting on the projects themselves. It’s really a focus on Indigenous pedagogy and we’re really thinking about how do we, as Indigenous people, approach the idea of education and what is education for? Being helpers to help others.”

On top of developing a broader curriculum, Reinhardt was a part of the development of the NAS major at NMU. He worked alongside faculty and staff in the CNAS, including Professor April Lindala, to get the major approved, which it finally was in 2016. Reinhardt was selected as graduation faculty commencement speaker that year and spoke to the graduates, who included the first group of students to graduate with a Native American Studies major in the state of Michigan.

“It was a big honor for me to be able to get up there at that time. To be able to give those words that provided some kind of locus for people on our relationship with the significance of that day, of what was happening,” Reinhardt said. “It was a moment of pride for a lot of people, and I was just honored to be able to represent, just humbled that I was there.”

His youngest daughter, Biidaaban, was part of the second class to graduate from NMU with an NAS major and his oldest daughter, Nimiinangos, has a minor in NAS. Both of them have been part of Reinhardt’s journey through Native American education, and he is proud of how they have incorporated that knowledge into their career paths of sustainable construction and being a family nurse practitioner.

While his family is an important part of Reinhardt’s life and way of being, he also considers many of the students and NMU to be a part of his family as well. He said that he considers many of his students to be his nieces and nephews, and he acknowledges that he has a responsibility to help them navigate their way through life and find their own success.

Working with students in the NASA has been an important part of Reinhardt’s legacy at NMU. In particular, he has assisted students with the continuation of the First Nations Food Taster fundraiser that he introduced during his time as director of the CNAS.

During the 2010 First Nations Food Taster event, Reinhardt started asking questions about the food, such as, “If our ancestors were here with us today, would they recognize this food as native food? Would it be familiar to them?” Many of the foods served, such as fry bread and green bean casserole, were questionable in their ties to the Native ancestors prior to colonization. Reinhardt soon flipped the question on its head to ask, “Would we be able to eat today like our ancestors ate then?”

Students and others within the CNAS engaged with this question until it became a fully-fledged idea known as the Decolonizing Diet Project (DDP). Reinhardt worked with the CNAS and NMU to gather a diverse group of 25 research participants who ate foods off of a master food list for a year. The master food list was carefully composed only of Indigenous foods that people in the Great Lakes region would have had access to prior to colonization.

In 2012, Reinhardt was one of two participants who were fully committed to eating 100% of their meals from the DDP food list. Overall, the 25 participants ranged from eating 25% to 100% of their food from the list and they all gathered to share meals, stories and their own personal journeys.

“I’m very proud of the work that we’ve done in the area for the Center for [Native] American Studies here in the area of Indigenous food sovereignty and research,” Reinhardt said. “We helped people create community around food. We found that the most intimate act that we do on a daily basis is eating together.”

Reinhardt plans to maintain and sustain that community as he heads into retirement. His main priorities are to complete the books he is currently working on, write some new books, spend time with his family and, of course, eat good food.

“I like the Center for Native American Studies’ [slogan] that ‘the gift is in the journey,’” Reinhardt said. “I’m still on that journey. I’m just going to play a different role. I’m learning how to be a good elder.”