It’s a natural phenomenon that will take your breath away. It’s something not everyone gets a chance to see in person in their lifetime. With green, red and sometimes purple lights, the aurora borealis, or northern lights, are an astounding sight. It’s highly recommended that one adds it to their bucket list if they haven’t seen them. Head professor of physics, David Lucas, Ph.D., recalled the northern lights that he saw in Ironwood, Michigan in the 90’s. “It looked as if something was going to come down on you, as if something was going to come out of the sky…One was like the heavens were opening. The other was like real big sheets of shimmering red-ish.”

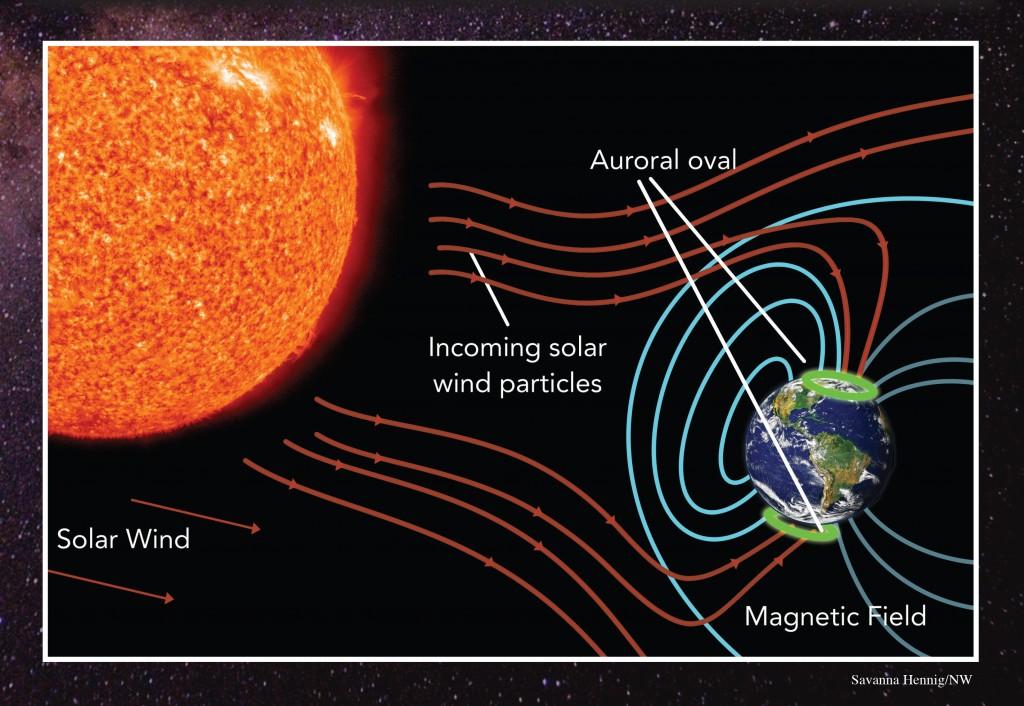

Physics professor David Donovan, Ph.D., has studied and recorded the lights in the past. The sun continuously emits high energy solar wind particles, which are made of charged particles like protons and electrons. “These particles take three to four days to reach the Earth,” Donovan said, racing at around one million miles per hour. As these particles approach Earth, they are moved around the protective magnetic sheath made by the Earth’s core. Imagine the field lines from a bar magnet. Field lines exit the magnetic north pole in the southern hemisphere and enter through the magnetic south pole in the northern hemisphere (note that the magnetic poles are different from the geological poles, which are opposite because of the flow of the magnetic field lines). According to Donovan, the shape of the magnetic field lines exposes areas where the charged particles from the sun can hit the molecules in our Earth’s atmosphere (see diagram below).

“They’re interacting with particles of the atmosphere, exciting them, much like [an electric] current excites a neon light,” Donovan said. These neutral molecules gain more energy by colliding with the excited particles of the sun. “Usually, things in nature tend to be at a lower energy state,” Donovan stated. “These excited particles in our atmosphere want to come back to ground [state] so they emit light.”

According to Donovan, the different colors that you see in the sky from the northern lights indicates the different elements in the atmosphere at that location, like oxygen and nitrogen. “While there are many ways to give electrons energy while they are bound to an atom, there’s only really one way to give up the energy, and that is to emit light.” The elements give up a photon of light, a form of energy.

“Near each of [the magnetic] poles, there is always a ring called the aurora oval,” Donovan said. “This is where these highly energetic particles are coming in.” Along the line of the oval is where the northern lights occur. “There are aurora ovals 24 hours a day,” Donovan said. Donovan stated that sometimes if there is a massive explosion on the sun, like a sun flare or an event called the coronal mass ejection, solar wind, which contains charged particles, are shot at the Earth much faster. This amount of energy makes it possible for the northern lights to be visible further south. “With higher energy you get a bigger ring. They [the excited particles] have more energy so they don’t get to a smaller ring.”

One popular belief has been that the northern lights are more active during the fall and spring. According to Donovan, contrary to popular belief the northern lights are active any time of year. They are not scientifically dependent on any particular season. “During the fall and spring, people are just out more and have a better chance at seeing them,” Donovan said. “I have seen them at all different times of year.”

Environmental studies and sustainability major Ryan Stephens, who has photographed the northern lights, uses one website to try to predict when the lights will be out. “I used www.spaceweather.com. They monitor everything going on atmospheric-related. Meteor showers, solar flares and geomagnetic storms…They give updates on this information.” Another website is www.softservenews.com, and you can also download smartphone apps, like Aurora Forecast. These sources can help you tell if there is or is going to be auroral activity.

There are unlimited places to view the northern lights in Marquette. One of the favorites for Stephens is Presque Isle, because of its proximity.

“There are tons of options there for [visual] compositions and getting an interesting perspective.” Stephens gave a few tips for photographing the northern lights, such as getting away from light pollution, avoiding moonlight and having a wide aperture on your lens. “My goal is to show people that the more time you spend outside, the more opportunities you give yourself to see more amazing things. It’s just an amazing natural wonder.”