The picture is of a broken building, holes in the wall from which a child and a man peer through at the camera. Garbage bags are strewn about, having been collected to salvage something, anything that could provide sustenance.

“These are the moments that make you ask yourself,” photojournalist Jared Kohler said, “‘Can I live with myself if I invade their trust to capture the moment?’”

When a protest turns bloody it can be felt by an entire country. When “the Syrian revolution” incited a violent reaction from its government, the country soon fell into instability. Violence sparked like wildfire, leading many to seek shelter in neighboring countries like Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. The event was described best by President and CEO of the International Rescue Committee David Miliband as “the largest humanitarian catastrophe of this century.”

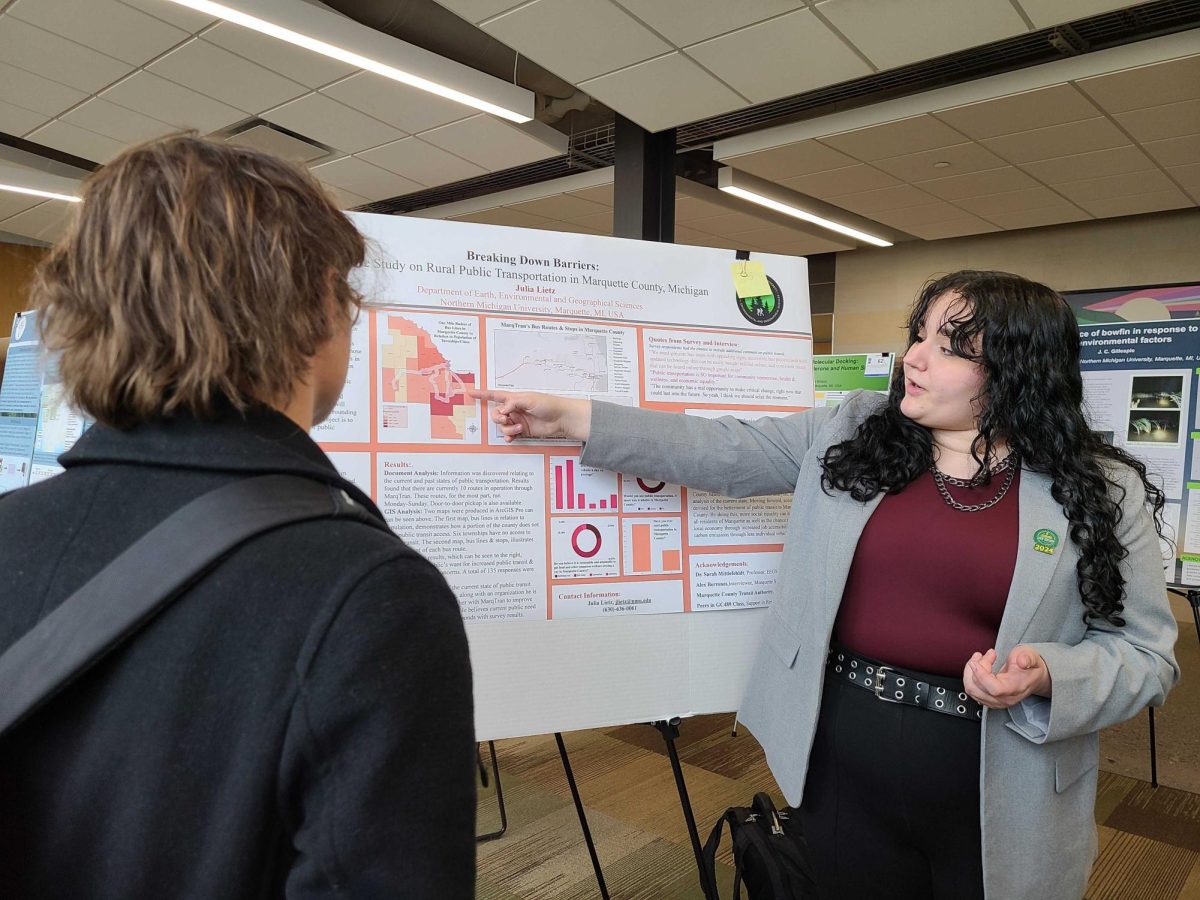

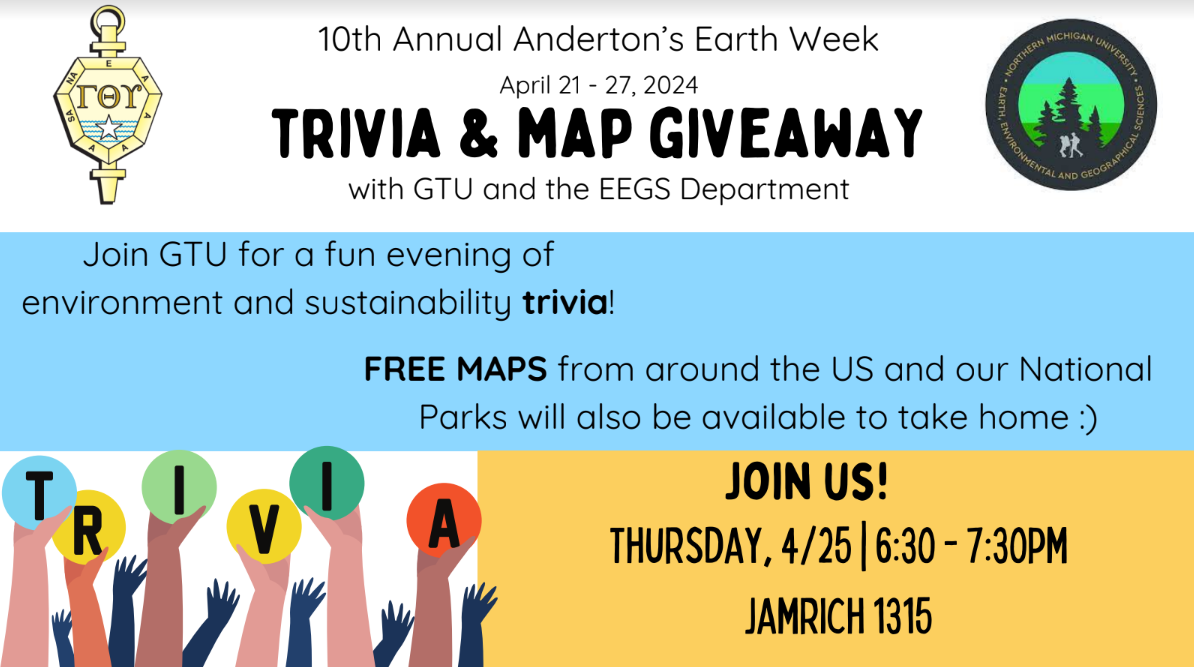

The Great Decisions Global Discussion series concluded Tuesday, March 24 when NMU students and faculty participated in a webinar discussion with Kohler. Through an assignment with a reporter from The New York Times, he saw the results of the Syrian crisis firsthand before he got involved with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 2013. Since then, Kohler has spent time in Jordan documenting the refugee crisis. He shared pictures, personal stories and clarified misrepresentations with participants like freshman Steve Wood, a political science major.

“It was more in depth than anywhere else in the mass media,” Wood said.

Kohler explained that the vast majority of the media portrayal of the crisis showed images from camps throughout Jordan and other countries in the Middle East. In 2012-13, 80 percent of the refugees didn’t go to refugee camps but instead lived in apartments or houses and tried to survive off of their savings.

“Jordan’s economy started to reel off of this weight,” Kohler said. “Many of these people we could identify with.”

Jordan’s government doesn’t allow the refugees to work, Kohler explained. While it wasn’t a pressing issue for many of the refugees initially as they had savings, most anticipated the conflict pushing them out of their home country for a few months at most. As reality set in and money dried up, many of the refugee children were forced to the streets to dig through trash or beg.

“The government is less likely to deport children,” Kohler said. “There is a lost generation.”

In the camps, life is a little better. While the Jordanian government has officially offered education and health care, there is a challenge presented by the shortage of space. There are many backgrounds suddenly forced together, and the teachers are ill-equipped to deal with the resulting issues, Kohler said. At the same time, there are not enough Jordanian teachers to educate the refugee youth, but the Syrian educators aren’t given job opportunities.

“They don’t want to see more competition in the workforce,” Kohler said.

For many refugees, life is so incredibly difficult that they return to a warzone in Syria. Kohler asked one family if it really made sense to return to whence they’d come. They replied it was better to die at home.

“Better a fast death than a slow one,” Kohler said. “This is one of the most depressing parts of the world.”

The Great Decisions Global Discussion series was brought to campus by the World Affairs Council of Western Michigan in collaboration with the International Programs Office at NMU. The events provided students, faculty and community members an opportunity to become educated about global issues, something that International Programs Director Kevin Timlin says is vital for educated people in the 21st century to do.

“We’re able to bring these types of issues here in a personal way,” Timlin said. “It’s something any university should allow.”