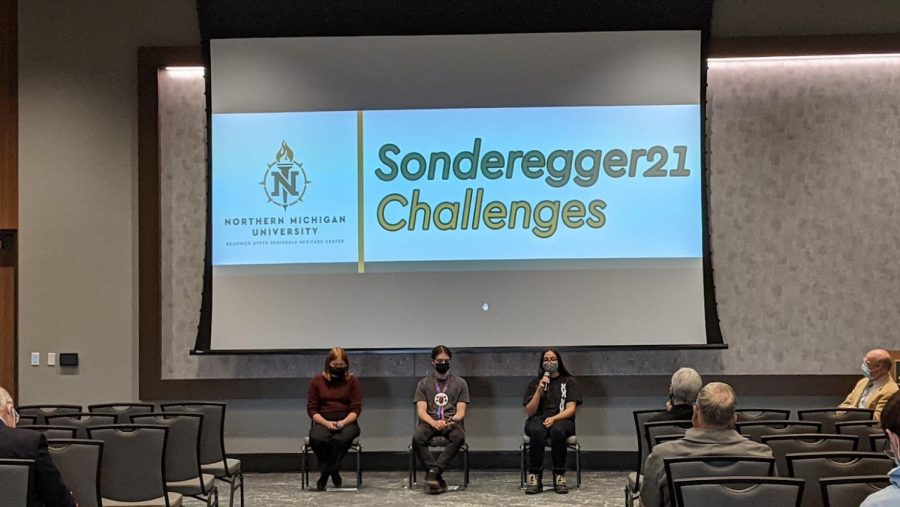

Student panel discusses intergenerational trauma for Native Americans

Yrsala Peterson, Bazile Panek and Kateri Phillips share their perspectives on intergenerational trauma as Indigenous people. As college students, they emphasized the healing their generation is doing following the struggles and trauma the generations before them endured.

November 18, 2021

Yrsala Peterson, a fifth-year music education major, was one of three Indigenous student panelists who sought to share not only their stories, but the stories of their elders at the annual 2021 Sonderegger Symposium on Nov. 5. The panel talked about intergenerational trauma among Native American communities and was one of many challenging topics featured at the conference.

“We’re just realizing that it’s not our fault. We are not the problem, these societal patterns are the problem,” said Peterson. “A lot of people when they think Native American, they have a very antiquated idea of what that term means and a very homogenized idea of what that term means. They think that all peoples within North America, all Indigenous peoples are very similar, which in fact, is not the case.”

The goal of the panel was to both make attendees more aware of intergenerational trauma as well as the reality and misconceptions that follow it. Intergenerational trauma holds different meanings for each individual person and various Indigenous communities.

“When it comes to intergenerational trauma, things are generalized too much,” Peterson said. “Every family, every tribe, every reservation has a different experience of what intergenerational trauma looks like, and a different approach to healing from it.”

The Sonderegger Symposium was hosted by the Beaumier U.P. Heritage Center and Center for Upper Peninsula Studies on Friday, Nov. 5 from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. and was offered both online and in-person at the Northern Center.

Its 21st year featured a variety of presenters and brought light to challenges in the U.P. that aren’t commonly voiced. These topics included “Air Bases of Northern Michigan and the Charlevoix incident,” “Keep the U.P. Wild” and the “Opioid Crisis (Past and Present).” To view the complete schedule and watch recorded sessions online, visit nmu.edu/upperpeninsulastudies.

The panel on Intergenerational Native American Trauma was one of 15 total sessions, but was unique in that it featured NMU students.

“A lot of the times when we’re talking about intergenerational trauma, we’re talking about the scourge of alcoholism and drug use on reservation, which I don’t think is a good way to characterize intergenerational trauma,” Peterson said. “[intergenerational trauma] about resiliency and about culture as a method of healing intergenerational trauma … we need more treatment centers on reservations, it’s true. Alcoholism, drug abuse, is rampant on reservations but I think that is a symptom of a deeper illness and culture is the method of curing that illness.”

Kateri Phillips, sophomore majoring in medicinal plant chemistry, was one of the other student panelists focusing on Native American intergenerational trauma.

“In my little world — I’ve filled so much of it trying to find these spaces and I don’t realize other people, how much they probably don’t see,” Phillips said.

Considering the intent of the symposium and all that it welcomed, Philips thinks of the ideal purpose of sharing their stories and reiterates it with her own wishes for the future.

“My hope for these events is that people take away and bring it into their own little worlds, because we’re all in our little separate bubbles, and we’re all kind of coming together. But if somebody can take that home, and then spread that maybe to their own, it’s like little seeds and it grows with the right soil,” said Phillips.

Bazile Panek, senior majoring in Native American studies and the third student presented on the panel, voices his own experience with intergenerational trauma and when he began to recognize it.

“As long as I can remember, I grew up on a reservation so I was very exposed to intergenerational traumas — effects on Indian people with alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, suicide. I was exposed at a very young age and have known about it ever since.”

Wishing to bring attention to places deserving of it, Panek introduced one of the struggles Native Americans face in regards to schooling and beliefs.

“I want people to understand that Native people especially are at a step back from everybody else when they attend college. You have to familiarize yourself with the western institution and then you can finally begin to be a student,” said Panek. “A lot of the times, it’s a responsibility for us to justify our existence as Native people first and foremost.”

He emphasized the fact that Native students, even if they do graduate high school and choose to attend college, rarely make it through that experience and complete higher education.

“Native students are less likely to attend higher education, and I think part of that is not only due to the disparities of being first-generation students or financial issues, but also the idea that education in the past is used to try to assimilate Native people through boarding schools,” Panek said. “That’s an issue that isn’t talked about enough, that Native students may have a problem with formalized education.”

Panek considers why these traumas aren’t really acknowledged, and explains that they do and have existed, as well as why he thinks that is.

“They don’t understand that trauma can and does carry through generations, especially when generations don’t put in the work to try to heal that trauma … blood memory has been a topic recently, that genetically, basically, we have traumas carried from past generations and we are predisposed to some trauma, like alcoholism, through our genetics,” Panek said. “Intergenerational trauma is real and people should believe it.”

Daniel Truckey, director of the Beaumier Heritage Center and organizer for the Symposium, found the topics of this year’s conference to be particularly important.

“The U.P. is going through a lot of changes right now, both good and bad. Or, it’s going through challenges, and those provide lots of opportunities for growth,” Truckey said. “They also provide a lot of opportunity for reflection on the past and what we’re trying to do in the future, and so that’s what we’re trying to do here today.”

He hopes that this symposium will continue to bring light to problems, such as intergenerational Native American trauma, in the future.

For Peterson, those future topics will hopefully include more depth on specific issues and bring in a wider diversity of speakers.

“I think that there are some deeper topics and intergenerational trauma that weren’t really touched on that I think we would have given a little more time,” Peterson said. “I think that it requires a little bit of a more intimate space to talk about those personal experiences, but I hope that we can get there one day and be more comfortable talking about them.”

Healing and hoping for understanding, Peterson also brings the discomfort of these topics to light.

“Native people are using learning as a method of healing from intergenerational trauma. When allies are willing to stand alongside us and learn with us, that helps lift us all up. So if you have the opportunity to learn about Native communities and Native culture, you’re helping us carry forward our own traditions as long as you’re doing it in a respectful way,” Peterson said. “Be willing to stand, and listen and be uncomfortable.”