Opinion—Land over landfill: composting helps reduce food waste

September 13, 2021

I was so excited for the dining hall to be open again, if only because it meant less take-out boxes and water bottles crowding the trash cans on every floor.

However, I was disappointed to discover that this semester the take-out boxes had been replaced by paper plates, paper cups and plastic cutlery. Even if these items are recyclable (if they don’t have food on them, which is very unlikely), there isn’t even an option to recycle the leftover items in the dining hall.

If you are not returning an actual dish to the dishwasher conveyor belt, the only other option is to throw everything in the three to six trash cans lining the door. Uneaten food, plates, untouched food, napkins, half-eaten food, plastic cups and more leftover food fill these trash cans multiple times a day.

This lack of reusable dishes in the dining hall can be largely blamed on the current understaffing of dining services and their inability to wash all the dishes going through the system. With an increase in student staffing, the dining hall might be able to consistently wash reusable dishes.

However, this still does not solve the problem of all the excess food being sent to the landfills every day.

According to Feeding America.org, nearly 40% of all food in America is wasted. At every stage in food production and distribution, unwanted and uneaten food is thrown away. This waste totals 108 billion pounds of food each year.

While lots of this food could, and should, be saved to feed hungry people, not all food is fit for human consumption. What happens to all that uneaten food thrown away in the dining hall.

This is food that is being left to rot among piles of dirty diapers, broken plastic and scraps of rusted metal in landfills. These other things cannot naturally decompose, but food has the special ability to return to the ground from which it came.

Instead of locking food scraps away in a landfill, we should be adding their nutrients back into the soil and continuing the natural cycle of life.

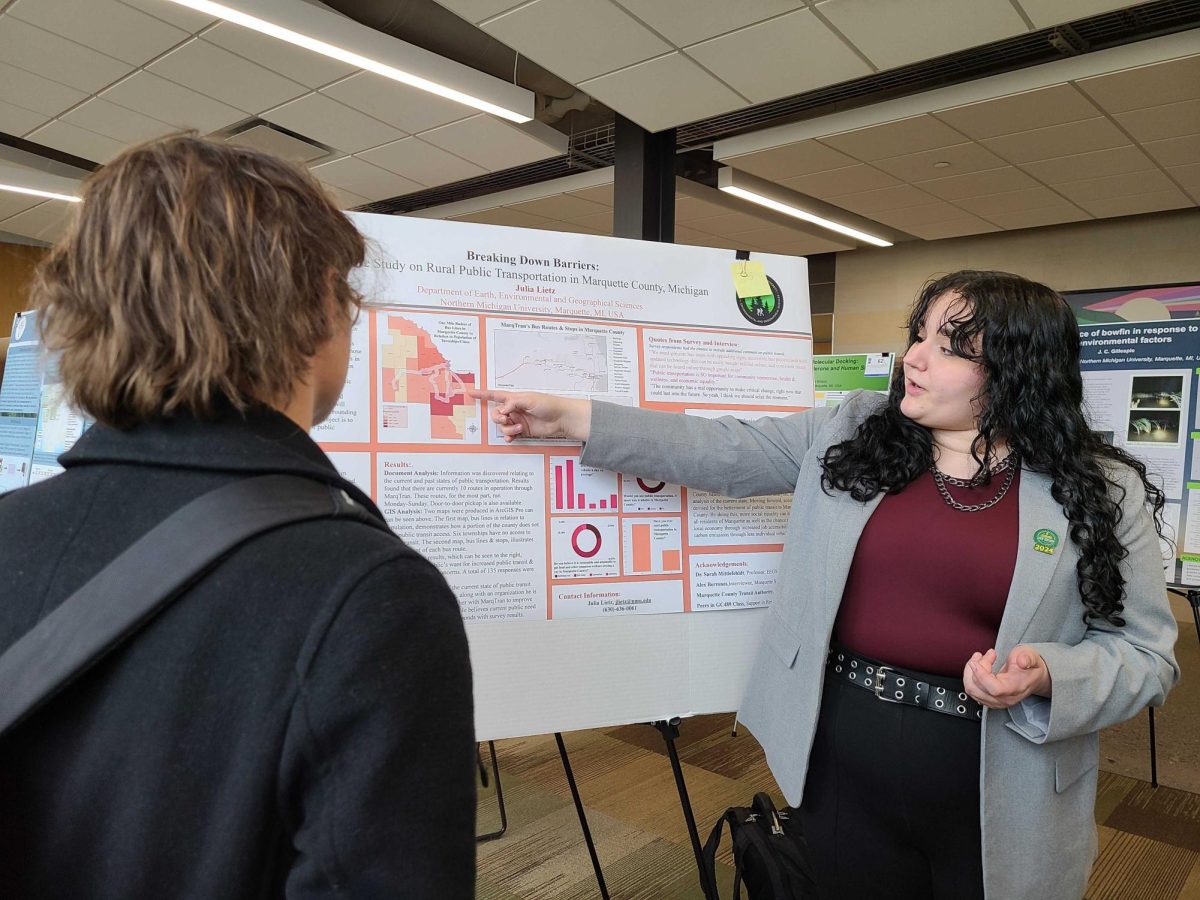

Continuing this cycle is something the hoop house is interested in doing on campus. They currently sell the produce they grow to Dining Services, including tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers and basil, and would like to get the unusable parts of that produce back.

“It would be really cool if in turn, the dining hall could give us their food scraps, which we could then compost and use in the soil to grow the plants to give back to the dining hall, like a cool cyclical exchange of goods,” senior co-leader of the hoop house Lovisa Kunkle said.

This is not terribly difficult to do. Most plant-based foods can be easily composted and turned into healthy soil with minimal effort. A compost pile collects food scraps where worms and bacteria do most of the work to break the food down into usable fertilizer.

The largest obstacle in the way of implementing a campus-wide composting system is education.

“A big part of [composting] is just educating people and making sure that we have the right signage,” sophomore hoop house co-leader Mary Kelly said. “Signage is a big thing just to make sure people are at least trying to put stuff in the right bins… just making it as easy as possible for people to put things in the right spots is central to this process.”

The best way for students to help reduce the amount of food heading to the landfill is to collect their food scraps and take them to the compost piles at the hoop house, located in the Jacobetti Complex. Compostable food scraps include things like eggshells, veggies and fruits, tea leaves and coffee grounds. However, meat and dairy should not be composted.

It takes a little more time to separate compostable food from recycling and trash, but the result is worth it. Helping return nutrients to the soil, where they can in turn grow more food is a valuable part of creating a sustainable future.